Letters from the Melting Pot

“There she lies,” says the hero, David Quixano, looking out over New York harbor, “the great Melting Pot—listen! Can’t you hear the roaring and the bubbling? There gapes her mouth—the harbour where a thousand mammoth feeders come from the ends of the world to pour in their human freight. Ah, what a stirring and a seething! Celt and Latin, Slav and Teuton, Greek and Syrian, black and yellow, Jew and Gentile, . . . the palm and the pine, the pole and the equator, the crescent and the cross—how the great Alchemist melts and fuses them with his purging flame! Here shall they all unite to build the Republic of Man and the Kingdom of God. Ah, Vera, what is the glory of Rome and Jerusalem where all nations and races come to worship and look back, compared with the glory of America, where all races and nations come to labour and look forward!”

Israel Zangwill, whose parents were refugees, described the almost unbelievable optimism of the immigrant. His play The Melting Pot was a runaway success when it premiered in Washington in 1908. President Theodore Roosevelt himself attended and was overheard shouting once the curtain fell, “That’s a great play Mr. Zangwill!”

The United States is an immigrant nation whose defining narrative is one of settlement and success. Behind that myth, however, there has always been a tension between those who have found success and the next group of immigrating settlers—between American ideals and the pernicious considerations of race and privilege. The Scripture says, “Love the stranger, for you were once a stranger in the land of Egypt,” but Americans, once established here, tend to forget their own past otherness and the Golden Rule along with it.

At the turn of the twentieth century, around the time when Mr. Zangwill was opening his play, the number of foreign-born people living in the United States reached a height unmatched until our own time. The way that Americans reacted to that demographic change offers a remarkably similar precedent to our own contemporary crisis. Here are seven stories of that era and its often baleful impact, and two remarks on where we stand today.

The United States did not get the message. During the First World War, the US Army worked with Robert Yerkes to test the intelligence of American soldiers, to identify potential officers and deserters, and the results were disconcerting: The average American, it turned out, was a “moron.” Moron was a pseudo-scientific classification introduced by H. H. Goddard for a mild intellectual disability. A moron had an IQ of 51-70, an imbecile had one of 26-50, and an idiot had one of 0-25.

Israel Zangwill, whose parents were refugees, described the almost unbelievable optimism of the immigrant. His play The Melting Pot was a runaway success when it premiered in Washington in 1908. President Theodore Roosevelt himself attended and was overheard shouting once the curtain fell, “That’s a great play Mr. Zangwill!”

The United States is an immigrant nation whose defining narrative is one of settlement and success. Behind that myth, however, there has always been a tension between those who have found success and the next group of immigrating settlers—between American ideals and the pernicious considerations of race and privilege. The Scripture says, “Love the stranger, for you were once a stranger in the land of Egypt,” but Americans, once established here, tend to forget their own past otherness and the Golden Rule along with it.

At the turn of the twentieth century, around the time when Mr. Zangwill was opening his play, the number of foreign-born people living in the United States reached a height unmatched until our own time. The way that Americans reacted to that demographic change offers a remarkably similar precedent to our own contemporary crisis. Here are seven stories of that era and its often baleful impact, and two remarks on where we stand today.

If we don’t plant the right things,

we will reap the wrong things.

It goes without saying.

And you don’t have to be,

you know, a brilliant biochemist

and you don’t have to have an IQ of 150.

Just common sense tells you to be kind,

ninny, fool. Be kind.

—Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

When the French psychologist Alfred Binet developed the first practical intelligence test, for placing schoolchildren in appropriate classes, he warned the world of its limitations. His test did not measure innate intelligence but only intellectual development. He understood that this was based on environmental factors, and therefore not generalizable to social groups or to the “racial hierarchy” which was accepted at the time.

The United States did not get the message. During the First World War, the US Army worked with Robert Yerkes to test the intelligence of American soldiers, to identify potential officers and deserters, and the results were disconcerting: The average American, it turned out, was a “moron.” Moron was a pseudo-scientific classification introduced by H. H. Goddard for a mild intellectual disability. A moron had an IQ of 51-70, an imbecile had one of 26-50, and an idiot had one of 0-25.

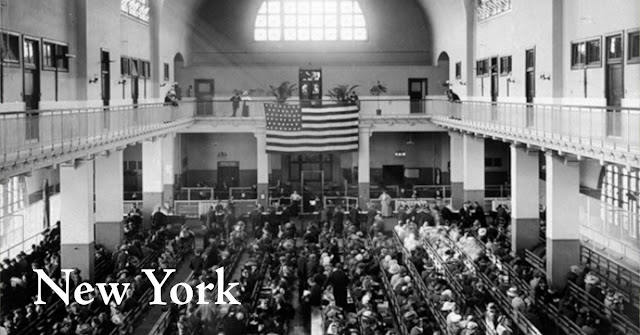

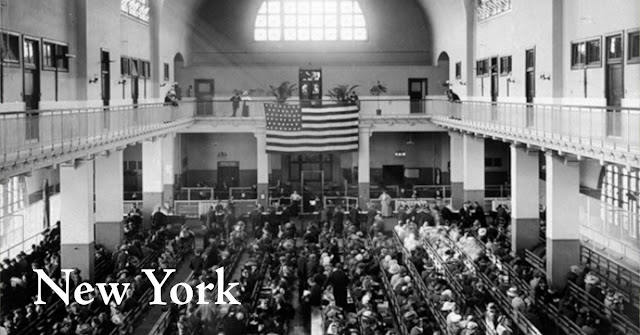

Goddard helped to establish an intelligence screening program at Ellis Island to identify “feeble-minded” persons. The test demonstrated an absurd cultural bias. The examiner would ask, “What is missing from the picture?” and show a photograph of an empty-handed man mid-swing in a bowling lane. That foreigners might not speak English or have seen a bowling alley only confirmed suspicions of their inherent stupidity. The program concluded that most of the study population was “feeble-minded,” including 83% of Jews, 80% of Hungarians, 79% of Italians, and 80% of Russians.

American studies of IQ in the early 20th century contributed to the growing eugenics movement and helped justify the forced sterilization of about 65,000 “feeble-minded” individuals and convicts. In confirming prejudices about a racial hierarchy based on innate traits, they lent a “scientific” basis to anti-miscegenation laws and convinced Congress to impose race-based restrictions on immigration in 1924.

Pale hands I loved

beside the Shalimar,

Where are you now?

Who lies beneath your spell?

—Laurence Hope (1865-1904)

The celebrity of “Lawrence of Arabia” helped launch an Arabian craze in 1920s America. “Young Americans affected Arab-style dress and crooned Arabesque love ballads.” Egyptian belly-dancing inspired the “hoochie coochie,” a sexually suggestive dance which moved from “The Street of Cairo” of the world’s fairs to become a mainstay of Roaring Twenties burlesque.

“Sun and sand” films, set in the deserts of Arabia and North Africa, packed the cinemas. The blazing star of the genre was an Italian-American actor named Rudolph Valentino, the original “Latin lover,” whose “elegant gestures and smoldering good looks” caused young women to faint in the aisles whenever he appeared on screen. Valentino in The Sheik (1921), The Eagle (1925), and The Son of the Sheik (1926) and the Mexican actor Ramon Novarro in The Arab (1924) and A Night in Cairo (1933) play charismatic and sensual bedouin princes who save, abduct, and problematically seduce reckless white women.

The Sheik was so wildly popular that the word came to describe a young man on the prowl, in the slang of the decade. The film also spawned a jazz standard, “The Sheik of Araby,” by Harry B. Smith and Francis Wheeler: “I’m the Sheik of Araby, / Your love belongs to me. / At night when you’re asleep, / Into your tent I’ll creep.”

But this was also an era of intensive racial classification, when 31 states held anti-miscegenation statutes and US legislation and legal verdicts had established Arab-Americans as “not quite white.” The transgressive racial implications of films like The Sheik were typically avoided by either killing one of the lovers or by revealing the hero to be an adopted European.

We’ll drink no more the beaming wine,

We’ll be no more its servile slave;

We’ll bow no more at such a shrine,

That makes a coward of the brave.

We’ll bow no more before a god

That rules us with an iron rod,

But drink from rills so pure and bright,

And sign the pledge right here tonight.

—J. M. Driver (1858-1918)

The last historic peak in immigration to the United States came at the end of the nineteenth century, when millions of Europeans fled poverty and violence in their home countries. The largest numbers arrived on Ellis Island from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Poland. By the turn of the century, fifteen percent of the American population was foreign-born. In Chicago every other person was an immigrant, and in New York every third.

The Temperance movement coincided with this surge in new arrivals. Evangelical Protestant revivalists of the Third Great Awakening harangued against alcohol as morally degrading and against alcoholics as sinners, while common opinion associated that vice, among many others, with immigrants.

Abstinence became a touchstone of American identity, and the political role of the Temperance movement was in its use as a symbol of the native and the immigrant, the Protestant and the Catholic, the middle class and the urban poor. In his New-York Tribune Horace Greeley described the former as “Working Men who stick to their business, hope to improve their circumstances by honest industry and go on Sundays to church rather than to the grogshop.”

From 1920 to 1933, the US prohibited “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” President Hoover’s “noble experiment” was not simply a naïve and paternalistic attempt at moral reform, but a coercive effort at cultural assimilation. Prohibition was a “symbolic crusade,” seen by American Protestants “as a way of solving the problems presented by an immigrant, urban poor,” whose culture was perceived as incompatibly alien and whose rising numbers threatened the privilege of native-born Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

America must remain American.

—President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933)

The 1924 National Origins Act placed an overall ceiling on European immigration of 165,000 annually, prohibited immigration from Japan, and established a quota system based on the percentage of each nationality already present in the US. About 3 million Germans had lived in the US in 1890, so the yearly quota for Germany after the signing of the Act was 51,000.

By tying these quotas on the 1890 census, the Act intended to turn back the clock on a recent influx of Italian immigrants, which it managed to reduce from an average of 200,000 per year in the early part of the century to a maximum of 3,845 in 1924. The law also expanded the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to exclude all people of Asian descent, and essentially blocked the arrival of non-white people by limiting immigration to those who were eligible for citizenship—only those nationality groups officially classified as “white” were so eligible.

Whiteness was a legal category with a conflicted past. In 1751, Benjamin Franklin warned that the yet unborn country would be overrun by “Stupid, Swarthy Germans,” that Germans were not white and could never assimilate to white American values. Franklin described “the Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians, and Swedes” as having “a swarthy Complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only excepted, who with the English, make the principal Body of White People on the Face of the Earth. I could wish their Numbers were increased.”

The American caste system pitted white against black, but most people occupied places between the two poles. By 1924, Germans and Swedes had officially become white, while Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians, Indians, Arabs, Jews, and the Japanese had not. White supremacists like Arthur de Gobineau described the newcomers as “the most degenerate races of olden day Europe... They are the human flotsam of all ages: Irish, cross-bred Germans and French, and Italians of even more doubtful stock.”

The immigration laws of 1882 and 1924 “represent the most drastic interventions to control the classification and complexion of new Americans,” and to restrict US immigration to white Protestants from Northern Europe. They reflect the racially-located anxieties of the ruling class, as well as white supremacist notions of a racial hierarchy understood to have achieved the peak of its “evolution” in the “Anglo-Saxon stock.”

“I think that we have sufficient stock in America now for us to shut the door,” said Senator Ellison DuRant Smith of South Carolina in 1924. “It is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries . . . We do not want to tangle the skein of America’s progress by those who imperfectly understand the genius of our Government and the opportunities that lie about us. Let us keep what we have . . .”

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

—Emma Lazarus (1849-1887)

The quotas established in the 1920s severely restricted immigration to the US at a time when millions of European Jews were in desperate need of asylum. Germany, with a Jewish population of 525,000, had an annual quota of 25,957. Poland, with 3.5 million, had a quota 6,524. Romania, with nearly a million Jews, had a quota of 377. The State Department did not view the quotas as goals but as limitations, and in 1939 and 1941 they established new and higher standards for vetting potential immigrants. Between 1933 and 1941, although many more German people were applying to immigrate than could be accepted, 118,000 German quota slots went unfilled.

At the time, refugees had no special legal status and were treated no differently than other immigrants. The American public remained indifferent, if not opposed, to their plight. Only one in four Americans favored the immigration of German refugees in 1938. In the wake of the Great Depression, they feared competition for scarce jobs and a burden on public services; in the early days of the war in Europe, they feared the potential national security risk of “enemy aliens.” Accordingly, the US Congress introduced more legislation to curb or end immigration than to expand it.

Antisemitism and anti-immigrant positions often overlapped. More than half of those who responded to a 1939 poll agreed that “Jews are different and should be restricted.” The voyage of the MS St. Louis is illustrative of these attitudes. The trans-Atlantic ocean liner, embarking from Hamburg with more than 900 German Jews, was turned back from the United States, Canada, and Cuba. A quarter of its passengers were later killed in extermination camps.

The Holocaust should have changed public opinion. Photographs and recordings of Nazi concentration camps and emaciated survivors appeared in American magazines, newspapers, and newsreels. However, in a December 1945 Gallup poll, only 5 percent of Americans were willing to accept more European immigrants than the nation had before 1942. Only with the crisis that followed the end of the war, with tens of millions of people displaced in Europe, did the US and the international community begin to create institutions to aid refugees.

We dance honoring ancestors

who claim our home,

and freedom to pursue our dreams

Our voices carve a path for justice:

Equal rights for all.

We prevail,

Our future harvested from generations.

From my life

opens countless lives.

—Janice Mirikitani (b. 1941)

Today Japanese-Americans make up less than a half a percent of the US population, and yet the influx of Japanese immigrants in the late-nineteenth century had a major impact on American policy and legislation, especially in California.

The severe social, economic, and agricultural disruptions of the Meiji era in Japan left millions of the most vulnerable without land or work. Between 1886 and 1911, more than 400,000 Japanese emigrated to the United States, most of them to Hawaii and the West Coast. The earliest arrivals became migrant laborers in the farms, mines, canneries, and railroads of the West. They later established shops, restaurants, and small hotels, first for their own community and eventually for the general public.

Californian prosperity and identity was constructed by a diverse and incalculable collection of people, including Japanese immigrants. By 1920, Japanese immigrant farmers in California produced 10 percent of its crop revenue. By the 1930s, the state had 40 Japantowns. Today there are only three, in San Francisco, San Jose, and Los Angeles, and a third of all Japanese-Americans live in those towns and Honolulu. What happened?

Resistance to Japanese immigration began in the early years of the twentieth century. Campaigns rehearsed the xenophobic tropes which had produced the Chinese Exclusion Act by portraying Japanese immigrants as a threat to American workers and American women, more loyal to the Emperor than the Union—“the brown toilers of the mikado’s realm.”

A series of deplorable policies ensued: barring Asian immigrants from owning Californian land in 1913, stripping citizenship from white women who married Asian men in 1922, imposing restrictions on immigration from Japan in 1908 and 1917, and explicitly banning Japanese immigrants in 1924. This led almost inexorably to the internment of between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese-Americans between 1942 and 1946.

Four Forty-Second Infantry

We are the boys of Hawaii Nei

We will fight for you

And the red white and blue

And will go the front

And back to Honolulu-lu-lu

Fighting for dear old Uncle Sam

Go for broke we don't give a damn

We will round up the Huns

At the point of a gun

And victory will be ours

Go for broke! Four Four Two!

Go for broke! Four Four Two!

And victory will be ours.

—“Go For Broke,” Fight Song of the 442nd

The 442nd Infantry Regiment was one of two all-Nisei fighting units active in the US military during the Second World War, along with the 100th Infantry Battalion. Comprised entirely of second generation Japanese Americans (and, by official decree, “white American” officers), it served in Italy, France, and Germany from 1943 to 1946. It is the most decorated regiment in US military history.

About two-thirds of the Regiment came from Hawaiʻi, where Japanese Americans made up 40 percent of the population and, despite frantic plans in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, proved too large and too integral economically to forcibly relocate. Nisei in the Hawaii National Guard were nonetheless stripped of their rifles, while the Hawaii Territorial Guard simply discharged them.

Those from the continental States were more used to racist fear, suspicion, violence, and systematic oppression. About 1,500 signed up directly from the internment camps—crowded tar paper barracks in the western desert. Stanley Hayami, a young artist who was later killed in Italy in 1945, wrote of his enlistment: “The army man… says that if we volunteer it’ll do a lot to show our loyalty and improve the relations and opinions of the American people toward us. It’ll show that we are truly Americans, because we volunteered despite the kicking around we got.”

The two groups did not get along, and there were fights in many units of the 442nd. The Hawai’ans called the mainlanders “katonks” for the sound an empty coconut made on hitting the ground, and the mainlanders called the Hawai’ans “buta-heads” (buta meaning “pig” in Japanese, though it is often written as “Buddhahead”). When some Hawai’ans visited the desert camps, they finally understood – all of them were fighting two wars.

“A Jap is a Jap,” said John DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, in 1943. “They cannot be assimilated,” said Senator Tom Stewart of Tennessee on the floor of the US Capitol in the same year. “There is not a single Japanese in this country who would not stab you in the back. Show me a Jap and I’ll show you a person who is inherently deceptive.”

The soldiers of the 442nd were heroes in Hawaiʻi, but racist attitudes, fears of the “Yellow Peril” and the “dual loyalties” of Americans who were not white, persisted in the continental US. Many veterans had trouble finding housing and employment, and they were often refused service in stores and restaurants. The American Legion did not permit Nisei to join until white officers from the 442nd intervened.

Stand beside her, and guide her

Through the night with the light from above.

From the mountains, to the prairies,

To the oceans white with foam,

God bless America, my home sweet home.

—Irving Berlin (1888-1989)

As an immigrant and a Jew, Irving Berlin was an unexpected bard for what has been called America’s second anthem—though Berlin himself denied that it was any such thing.

Ragtime hits on Tin Pan Alley earned him fame and a conscription notice from the US Army—“Army Takes Berlin!”—to write jingoistic ditties for Woodrow Wilson. “God Bless America” was written at this time, though not performed until 1938 when Kate Smith, the First Lady of Radio, needed a patriotic song to honor Armistice Day. The lyrics were exquisitely simple, naively patriotic, and deeply personal: “To me, ‘God Bless America’ was not just a song but an expression of my feeling toward the country to which I owe what I have and what I am.” He assigned all royalties to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of America.

Ragtime hits on Tin Pan Alley earned him fame and a conscription notice from the US Army—“Army Takes Berlin!”—to write jingoistic ditties for Woodrow Wilson. “God Bless America” was written at this time, though not performed until 1938 when Kate Smith, the First Lady of Radio, needed a patriotic song to honor Armistice Day. The lyrics were exquisitely simple, naively patriotic, and deeply personal: “To me, ‘God Bless America’ was not just a song but an expression of my feeling toward the country to which I owe what I have and what I am.” He assigned all royalties to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of America.

Berlin, born Israel Beilin and in Siberia, had arrived at Ellis Island in 1893 with his parents and five siblings. None of them spoke any English. They were among the two million Jews to immigrate to the US from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1914, fleeing the bloody pogroms of the Russian tsars. Many, including Berlin, the Gershwins, and the four eponymous Warner Brothers, made inestimable contributions to American life and culture. So did many of the children of that first generation, including Leonard Bernstein, Noam Chomsky, Kirk Douglas, Milton Friedman, Stanley Kubrick, and the poet Howard Nemerov.

The

story of our struggle has finally become known. We lost our home, which

means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which

means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our

language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of

gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives

in the Polish ghettos and our best friends have been killed in

concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives.

Nevertheless, as soon as we were saved—and most of us had to be saved several times—we started our new lives and tried to follow as closely as possible all the good advice our saviors passed on to us.

—Hannah Arendt (1906-1975)

Hannah Arendt arrived in New York in May 1941. Having been good Russians in Russia, the Jewish immigrants set out to be good Americans in America. Her crash course took place at a family home in Massachusetts, where she chafed against a ban on smoking in the home. The formidable German intellectual first frequented the garden, alongside the husband of the home, though she later negotiated the right to smoke in her room.

“If patriotism were a matter of routine or practice, we should be the most patriotic people in the world,” wrote Hannah Arendt of a later wave of Jewish refugees. “But since patriotism is not yet believed to be a matter of practice, it is hard to convince people of the sincerity of our repeated transformations... The natives, confronted with such strange beings as we are, become suspicious; from their point of view, as a rule, only a loyalty to our old countries is understandable. That makes life very bitter for us.”

Arendt observed that for the Jewish immigrant, the path of the "assimilated minority" was a trap. In her 1943 essay "We Refugees," she rejected the figure of the "parvenu"—the frantic social climber who tries to out-American the Americans through an erasure of self. Instead, she championed the "conscious pariah." For Arendt, to be a pariah was to accept one's status as an outsider and turn it into a cosmopolitan strength. She cited other ostracized Europeans like Franz Kafka, who used their difference "to transcend the bounds of nationality and to weave the strands of their Jewish genius into the general texture of European life."

The struggle for identity was of course only a prelude to the fight for survival against totalitarianism, the subject of Arendt's later work. She argued that the 18th-century Enlightenment ideal of the Rights of Man, given by nature and inalienable to all human beings, had been finally extinguished in the gas chambers of Central Europe. In practice, the only rights which an individual possessed were those granted by the state. The refugee, having lost her political community, has therefore lost her "right to have rights." And in a world defined by borders, humanity alone does not grant a passport.

Nevertheless, as soon as we were saved—and most of us had to be saved several times—we started our new lives and tried to follow as closely as possible all the good advice our saviors passed on to us.

—Hannah Arendt (1906-1975)

Hannah Arendt arrived in New York in May 1941. Having been good Russians in Russia, the Jewish immigrants set out to be good Americans in America. Her crash course took place at a family home in Massachusetts, where she chafed against a ban on smoking in the home. The formidable German intellectual first frequented the garden, alongside the husband of the home, though she later negotiated the right to smoke in her room.

“If patriotism were a matter of routine or practice, we should be the most patriotic people in the world,” wrote Hannah Arendt of a later wave of Jewish refugees. “But since patriotism is not yet believed to be a matter of practice, it is hard to convince people of the sincerity of our repeated transformations... The natives, confronted with such strange beings as we are, become suspicious; from their point of view, as a rule, only a loyalty to our old countries is understandable. That makes life very bitter for us.”

Arendt observed that for the Jewish immigrant, the path of the "assimilated minority" was a trap. In her 1943 essay "We Refugees," she rejected the figure of the "parvenu"—the frantic social climber who tries to out-American the Americans through an erasure of self. Instead, she championed the "conscious pariah." For Arendt, to be a pariah was to accept one's status as an outsider and turn it into a cosmopolitan strength. She cited other ostracized Europeans like Franz Kafka, who used their difference "to transcend the bounds of nationality and to weave the strands of their Jewish genius into the general texture of European life."

The struggle for identity was of course only a prelude to the fight for survival against totalitarianism, the subject of Arendt's later work. She argued that the 18th-century Enlightenment ideal of the Rights of Man, given by nature and inalienable to all human beings, had been finally extinguished in the gas chambers of Central Europe. In practice, the only rights which an individual possessed were those granted by the state. The refugee, having lost her political community, has therefore lost her "right to have rights." And in a world defined by borders, humanity alone does not grant a passport.

i want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you

to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans

drown

save

be hunger

beg

forget pride

your survival is more important

no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying—

leave,

run away from me now

i dont know what i’ve become

but i know that anywhere

is safer than here

—Warsan Shire (b. 1988)

Today the foreign-born population of the US is at its highest point in a hundred years. Historic peaks in immigration, both now and at the turn of the twentieth century, inspire a predictable set of reactions: overtly racist categorization, attempts to force assimilation, and legal obstacles to further immigrants. The racial quotas established in 1924 reduced the foreign-born population of the US from 15 percent in 1900 to less than 5 percent by 1970. Those quotas remained substantially in place until 1968. Since then the foreign-born population has risen again, reaching 13.4 percent in 2015, with most immigrants arriving from Latin America and Asia.

Whatever changes are made to immigration law in the next two years, they will come too late to alter the trajectory of the US towards a majority-minority state where no one racial group can claim a majority. Today 60 percent of Americans identify as “having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa, or, in another word, white, but this is expected to fall to below 50 percent by 2045 due to long-term demographic trends. Americans under 18 years old will be majority-minority in 2020.

Fears of demographic change lead to the idea that social cohesion must be based on cultural (a shorthand for ethnic, religious, and often racial) homogeneity. Officials associated with the current presidential administration have asked for ways to “vet for culture” (Jeff Sessions) or “screen for integration potential” (Jean Hamilton) when relocating refugees to the US. However, most historical instances of social disintegration result from political, ideological, economic, and class differences, rather than cultural ones.

Opponents of immigration speak of crime (most research suggests that immigration either does not effect the crime rate or else reduces it), immorality (a code-word for unfamiliarity), and the inability of alien peoples—Germans, Irish, and Poles in the nineteenth century, Jews and Japanese in the early twentieth, and Muslims and Latin Americans in the twenty-first—to assimilate American values. The fact that the former groups are today accepted as a part of the American tapestry is a sign of how absurd those arguments really are.

American prosperity rests on its ability to integrate diverse people on the basis of civic principles of liberty, equality, participatory government, and justice of law—principles which have nothing to do with ethnicity, creed, or national origin. The

world is strengthened by our differences, not defined by them. We

are each enriched in a particular way by the people we encounter who

are authentic, unique, and distinct from ourselves because they are

true to themselves. They

need not threaten us: human

complexity

is not a zero-sum game or

a “negative mirror” but a symphony.

Rhythms we expressin similar to our ancestors

It’ll answer your questions if you understand the message

From the days of the slave choppers, to the new age of prophets

As heavy as hip-hop is I’m always ready to drop it

From the mind which is one of Allah’s best designs

And mines’ll stand the test of time, when I rhyme.

—Rakim (b. 1968)

Islam intersects with hip-hop in ways that reflect urban life, historical movements and powerful messages. Muslim rappers in North America include: (1) converts like Ice Cube, Raekwon from Wu-Tang Clan, Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest, Brother Ali, and Yasiin Bey, once Mos Def; (2) second generation Muslims like Chali 2na from Jurassic 5 and Lupe Fiasco; and (3) immigrants like Iraqi-Canadian Yassin Alsalman (Narcy), Syrian-American Omar Offendum, and DJ Khaled, born in New Orleans to Palestinian parents.

The relationship between Islam and hip-hop, at least for the first two categories, is often knitted through the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and the Five-Percent Nation of Clarence 13X. Islam centered a challenge to whiteness as a “Western” ideal. It allowed African-Americans, especially those descended from the men and women dragged in chains and horror from West Africa, to assert an identity independent of that given by the slaveholders of the United States.

Until his martyrdom Malcolm X sought to reconnect African-Americans with an African identity through Islam. “He saw in this the road to a new sense of group identity, a self-conscious role in history, and above all a sense of man’s own worth which he claimed the white man had destroyed in the Negro,” wrote Alex Haley, co-writer of his Autobiography.

“So early in life,” said Malcolm X (who is to me the archetype of truthfulness), “I had learned that if you want something, you had better make some noise.”

Footnote: for really interesting expert content on the experiences and achievements of Black Muslims in the United States, check out Sapelo - https://sapelosquare.com/

ReplyDelete