Letters from Eastern Europe

Nationality cannot be observed in the blood, nor in the soil, nor even on the tongue. “Nationality exists in the minds of men,” a Dutch historian explained, in the wake of the last Great War. “Outside men’s minds there can be no nationality, because

nationality is a manner of looking at oneself not an entity as such.

Common sense is able to detect it, and the only human discipline that

can describe and analyse it is psychology. . . . This awareness, this

sense of nationality, this national sentiment, is more than a

characteristic of the nation. It is nationhood itself.”

Nations, in other words, are not natural entities but social constructs, like race or

gender, resting on sometimes insidious assumptions about the essential characteristics of their members.

Today a revival of nationalism is reshaping the postwar order of Europe. These nationalist impulses emerge from a basic human desire for the perceived safety of a strong group identity, and for perceived homogeneity within that group. As the world’s economic systems show their

faults, as migration reshapes the demographics of the continent (and not for the first time), the future of the

European project grows less certain.

However, historical and contemporary realities reveal a global integrity

that nationalist narratives cannot explain. Local achievements are the products not only of local ethnic groups but of regional interactions and exchanges. The movement of people and ideas across territorial lines, borders we now regard as fixed, is not some recent phenomenon but rather the norm. The nations of modern Europe could not have come into being without it.

Zniknął smutek ponury, a radość panuje;

Zbawiony Naród słodkiey używa swobody.

Gloomy sadness is gone, carefree joy holds sway.

The rescued nation hails sweet freedom’s holiday.

—Jewish hymn for the Third of May celebrations, 1792

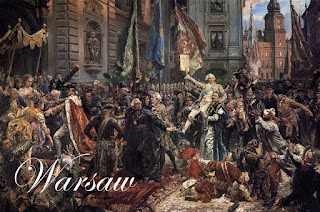

On the third of May 1791, in the Senate Hall of Warsaw’s Royal Castle, the deputies and senators of the Four Year Sejm and King Stanisław August approved a constitution. It was Europe’s first democratic constitution, preceding that of Revolutionary France by four months. The document reflects the primacy given by the Enlightenment to reason, rule of law, and personal freedom, including ultimately unsuccessful efforts by Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski to extend the rights of man to the Jewish nation.

The 1791 constitution remains a powerful symbol of peaceful and democratic political transformation, but also of the gridlock that participatory government implies. The Sejm, the bicameral parliament of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, accepted the necessity of reform only after a century of inaction led to the disaster of 1772, when their atrophied nation was divided up like a cake between its modernized neighbors. In the words of the Polish proverb, “Polak mądry po szkodzie”—A Pole is wise when the damage is done.

The success of the new constitution infuriated Poland’s autocratic neighbors. Russia invaded within weeks of its first anniversary, and this Second Partition reduced Poland to a third of its former self. In 1794, Tadeusz Kościuszko, a hero of the American Revolution, led a failed uprising against the occupation of Polish lands. With his capture at Maciejowice (“Finis Poloniae!”) and the massacre of Warsaw’s Praga suburb, Poland ceased to exist as an independent state. It would not reappear on maps of Europe for 123 years.

The Polish kingdom is:

Paradise for Jews,

Shelter for heretics,

Harvests for foreigners,

Fatherland for immigrants.

—Regnum Poloniae, mid 17th cen.

Jews began arriving in Lublin in the fourteenth century; by the twentieth, one in three Lublinites was Jewish. A medieval ban on living within the walled town placed most Jewish houses in a notch between the Grodzka Gate and the castle hill, but there they thrived. Lublin became known as the Jerusalem of Poland for the size of its Jewish community, and as the Jewish Oxford for the high degree of learning.

Under the statue of Bolesław and the privileges granted by Kazimierz III, the Jewish people of medieval Poland enjoyed greater legal autonomy, freedom of worship, freedom to trade, and protection from violence than anywhere else in the Ashkenazi diaspora. Other Christian nations, which dealt with Jews only as subjects and scapegoats, despised the Polish Commonwealth as a paradisus judaeorum. And many European Jews, fleeing persecution and overpopulation in Bohemia, Moravia, and German lands, made their home there.

However, the dependence on royal protections, along with an exemption from Christian proscriptions against practices like usury, pressed Jews into dangerous positions. Jews became moneylenders and managers, traders and taverners, caught between the greed of the szlachta, the Polish nobility, and the desperation of the peasantry. They received the blame for the hardships of both.

In 1648, the Khmelnytsky cossack rebellion targeted Jews alongside nobles and the Catholic clergy as enemies of the people, with a brutality chronicled in Natan Hannover’s “Abyss of Despair.” It was neither the first nor would it be the largest of Eastern Europe’s many pogroms and massacres. Today, in the notch between Lublin’s old town and castle, there is nothing but asphalt and lawn.

Postnote: In the midst of the crises of the early modern period, the

reformers of the Polish Enlightenment sought “a way to turn Polish

Jews into citizens useful to the country,” in the words of one

deputy of the Sejm of 1788. Leaders tried integration through

economic and legal reforms and military conscription. They called on

Jews to join in the industrialization of Poland and the insurrection

against the partitioning powers, and many answered that call. However

the perception of a rift between the two “nations” remained. The

conservative Wincenty Krasiński wrote in 1818, “The Jews are an

insurmountable problem!”

Feed me please from this red-red stuff.

—Genesis 25:30

It began in England, with a set of events that became archetypal.

A Christian child went missing, was found murdered. A Christian mob

accused a Jew and the Jews of ritually using or consuming the blood

of the victim. A local leader perpetuated the slander, to consolidate

political and economic power. A trial occurred, based on wildly

circumstantial evidence, “miracles,” and statements forced by

torture, followed by the massacre of Jewish families and

neighborhoods, ending in the expulsion of English Jews in 1290.

The history of antisemitism in Europe is tied to a history of

invented accusations, including the infamous blood libel: the lie

that Jews used Christian blood for rituals. It spread like a virus

from England to France to Central and Eastern Europe. The Spanish

Inquisition made use of it in the fifteenth century, and the Ottoman

Sultan had reason to firmly denounce it in the sixteenth. Jewish

communities across Europe received exemptions from the need to use

red wine in religious rituals, for fear of exciting suspicion. (The

fact is that Jewish mitzvah not only prohibit murder and human

sacrifice, but “the blood of no manner of flesh” is considered

kosher.)

In the modern period, the blood libel has fueled the antisemitic

propaganda of the Russian Empire, the Third Reich, and Hamas. The

libel against Jews retains its hold on as many as one in ten Poles,

according to a 2009 survey, especially in less urbanized and less

educated areas east of the Vistula. In Belarus, Russian

dezinformatsiya extended the accusation of blood-drinking to

Ukrainians during the 2014 war.

The consensus of many centuries . . .

that the earth remains at

rest

in the middle of the heaven as its center

would, I

reflected,

regard it as an insane pronouncement

if I made the

opposite assertion:

that the earth moves.

—Nicolaus

Copernicus (1473-1543)

Until Copernicus made this bold pronouncement, the earth was the

center of the universe. Born to a merchant family in Polish Prussia,

he spoke German, Polish, Italian, Greek, and Latin—and Latin was

the language of the day. He studied at the Jagiellon University in

Kraków before traveling to the Natio Germinorum, the world’s first

institute for higher learning, in Bologne and to the University of

Padua. By the time he earned his doctorate, he possessed all the

knowledge of his day in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and

theology, including of Ptolemy’s geocentric account of the cosmos,

which he found unsatisfying.

His De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) was a turning

point in the history of science. It sought to prove, through

observations and calculations, that the earth is a sphere and that it

moves around the sun. In accounting for the diurnal motion of the

stars by the rotation of the earth, the Copernican Revolution deposed

the earth from its place as universe’s stationary center. Ours is

only one world among many.

The bold shift away from a geocentric cosmos faced a stiff

resistance, namely Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and his assistant Johannes

Kepler (1571-1630), who insisted that the the sun orbited the earth

and the planets orbited the sun. However, the telescope of Galileo

Galilei (1564-1642) and the classical mechanics of Isaac Newton

(1652-1727) finally showed that not only was the earth but one planet

among many, but the sun also was only a solitary star.

Nie ma reguły bez wyjątku.

There is no rule without an

exception.

—Polish proverb

On March 11, a new Polish law banning all trade on Sunday took

effect, with some exceptions. Hospitals and pharmacies remain open

for obvious reasons, as do gas stations for the sake of a modern

transportation system. Ice cream parlors and flower shops have a less

intelligible dispensation as businesses which traditional Polish

families love to visit on Sunday. Stores at airports and train

stations are likewise allowed to stay open, and so are cafes and

bakeries. The law left many Poles looking stranded (and hungover) in

front of shuttered supermarkets, in spite of sensational media

coverage, and set many businesses searching for a loophole.

It was easy enough for McDonald’s, Burger King, and KFC to call

in favors as traditional Polish cafes—they all stayed open.

Shopping malls next to train stations began to call themselves train

stations, with mixed results. Gas stations have taken advantage of

their exemption to start expanding adjacent convenience stores into

butchers, delis, and brick oven pizzerias. Other smaller stores

installed brand new bread ovens, declared themselves bakeries, and

gained a monopoly on Sunday cigarettes. Everyone else who wants to

make a few złotys just sits at home and steams.

Poland’s conservative ruling party, Law and Justice, along with

the Solidarity trade union and the Catholic church, intended to

protect workers and assert traditional values. Instead the Polish

government finds itself in the absurd positions of forcing Muslims to

stop selling kebab because of the Christian sabbath while allowing

almost everyone else to sell “traditional” Polish Big Macs, Zara

shirts, gelato, tulips, and zapiekanka.

(Germany and Austria both have similar laws, with the chance for

larger enterprises to pay for exemptions. Hungary’s Sunday ban

lasted from 2015 to 2016. Poland’s is popular with 51 percent of

voters, according to a national survey.)

Kde se pivo vaří,

tam se dobře daří.

Where beer is brewed,

life is good.

—Czech proverb

Of Europe’s many fault lines, one of the most telling is that of

beer and wine: a diagonal rift which leaves the grape to the French,

the Italian, and the Iberian, and the hop and grain to the German,

the Briton, and the Slav. Home-brewed beer was a historic source of

calories, hence the Czech term “tekutý chléb” (liquid bread),

the proverbial rhyme “Pivo dělá hezká těla” (Beer makes good

bodies), and the Pan-Slavic toast “Na zdravi!” (To your health!).

Czech brewers and the technology and ingredients they used have

had a deep impact on brewing culture not only in Europe but around

the world, where Czech-style bottom-fermented lagers have become the

standard commercial beer. Bohemian hops and Moravian barley were the

best in Europe for centuries, and the brewing textbook of František

Ondřej Poupě directed the beer culture of the Enlightenment.

Today Czechs consume more beer than anyone—an annual average of

300 pints per person, compared to 160 in the US. While communist

nationalization of the industry decimated Czech breweries, the number

has tripled in the last decade, and many of the additions are local

microbreweries.

The pale gold, foamy, and aromatic Czech lager is the most common,

including the ubiquitous pilsner (from the Bohemian town of Plzeň or

Pilsen), but there are also black lagers (Černý pivo), which can be

dry and sharp or bittersweet and smoky. Beers in the Czech Republic

are often labeled by density, where a typical 10° light lager has a

4% higher density than water (and about 4.5% ABU).

The simulacrum lifted its sleepy

lids and saw forms and colors

it did not understand, and lost in sounds

it rehearsed fearful movements.

Gradually, it saw itself (as do we)

imprisoned in this sonorous web

of Before, After, Yesterday, Meanwhile, Now,

Right, Left, I, You, Those, Others. [...]

The Rabbi observed it with tenderness

and with some horror. “How” (he asked)

“could I beget this sorry son

and abandon inaction, wherein sanity lies?”

“Why did I add to the infinite

series another symbol? Why to the vain

skein that winds in the eternal

did I give another cause, an effect, and grief?”

In the hour of anguish and lack of light,

his eyes on his Golem would rest.

Who will tell us the things God felt

when looking at his rabbi in Prague?

—Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986)

In Prague, the City of a Thousand Spires, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel made a golem out of clay from the Vltava and incantations in Hebrew. The word golem comes from the Bible; it means “raw,” an unfinished human form, passing into Hebrew and Yiddish as an insult for someone clumsy, slow, and dumb. The golem of Prague was all these things.

Many stories surround this archetypal monster of the sixteenth century, but in the main he defended the Jewish neighborhood of Prague from antisemitic attacks. In some he had a name, in others he fell in love or rampaged violently through the city, and in one Rabbi Loew forgot to deactivate the golem on Friday evening and nearly desecrated the Sabbath. The body of the golem is said to lie in the genizah of the New Old Synagogue, one of the few to survive the War, and indeed it is said that the Nazi who entered there perished at at the golem’s dumb hands.

The golem is now a mainstay of popular culture, starring in Gustav Meyrink’s famous 1914 novel Der Golem, in the silent films they inspired, and in Elie Wiesel’s children’s book. It has appeared in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, Dungeons & Dragons, Marvel and DC Comics both, and “The X-Files.” In the classic two-part Czech comedy Císařův pekař a pekařův císař, released in the midst of the Cold War, the Emperor’s desire to find and use the mythic golem symbolizes the race for nuclear power.

What is the sum of the privations,

the labours and the grief of

man,

of past, of future generations,

compared with just one

minute’s span

of all my untold tribulations?

What is man’s

life? his labour? why—

he’s passed, he’s died, he’ll pass

and die . . .

his hopes on Judgment Day rely:

sure judgment,

possible forgiving!

but my sorrow is endless, I

am

damned to sorrow everliving;

for it, no grave in which to

doze!

sometimes, snakelike, it creeps or glows

like flame, it

crackles, blazes, rushes,

or, like a tomb, it chokes and

crushes—

a granite tomb for the repose

of ruined passions,

hopes and woes.

—Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841)

One time the devil tried to dam up the Senice River. Being the devil, he

could only work at night, and every night he piled up stone into a

wall on the hill over Lidečko, and at the break of every dawn he

returned to the shadows under the earth. The wall was almost

finished, but cockscrow always found him too early; so the devil sent

out his imps to buy up all the roosters in town.

From door to door they went, always paying high, for everyone

knows that the devil is no stranger to wealth, and they bought up

every rooster in the valley but the one belonging to a poor old

woman, who took one look at the imp, saw him for what he was, and

slammed the door, for everyone also knows that old women are the

strongest among us. The devil worked through the night, but in the

early hours the old woman’s rooster crowed, the town awoke, and the

devil vanished, leaving a transversal crack in his bench of sandstone

through which the Senice continued to stream.

The hills of Eastern Europe abound with Devil’s Rocks (Čertovy

skály in Czech) and with stories of the devil at work among the

hills, the birch forests, the streams, and the villages of foolish

men and wise old women. The character of the devil, familiar from the

Bible, runs through Slavic literature, related piecemeal to

pre-Christian entities. The porcine trickster called the Black One

(Chort in Russian and Čert in Czech), son of Chernobog and Mara,

tries to tempt people off the narrow path. The Leshy (“[he] of the

forest”) leads travelers and children astray in a more literal

sense. The inherently protective but irascible home devils or domovoy

inhabit the hearth and turn more demonic at the sight of bad behavior

and the sound of foul language.

Rompu, rompu la murojn inter la popoloj!

Break, break the walls between the peoples.

—L. L. Zamenhof (1859-1917)

When Ludoviko Lazaro moved to Warsaw, he realized that he was a Jew. Born in a Polish city under the Russian Empire, the son of a teacher of German and French and a Yiddish-speaking housewife, he felt himself affiliated with them all and with humanity first of all; but when others in Warsaw saw him, they saw and dealt with him as Jewish and nothing more, and when he saw others, he learned to see not fellow human beings but Russians, Poles, Germans, and Jews.

Zamenhof was driven from childhood by the conviction that the hostility which obtained between nations, despite the plurality of individuals, was due to the lack of a common language, and that none of the existing languages would serve. From secondary school, he began fashioning a new language, a “lingvo internacia,” borrowing most words from the Romance and Germanic families, principally Italian, French, German, Yiddish, and English, and only a few from the classical ones or from Polish, Russian, or Lithuanian, despite his familiarity with these.

“Today,” said Zamenhof at the First World Congress of Esperanto in 1905, “there meet not Frenchmen with Englishmen, not Russians with Poles, but humans with humans”—or, in the original Esperanto, “sed homoj kun homoj.”

While it never became as universal as Zamenhof hoped, nor could it blunt the great carnage caused by twentieth century nationalism, Esperanto is the most successful constructed language by far, with around a million speakers worldwide (including Ho Chi Minh, Tito, Bahá'u'lláh's son `Abdu'l-Bahá, George Soros, and William Shatner).

In the Praga Manifesto of 1996, advocates of Esperanto point to the fundamental inequality of a world where the common language of communication is native to a privileged few (English-speaking countries account for 6 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of its wealth), while the rest can attain a secondary competency only after years of effort. They point out how study of the English language centers itself on the culture, geography, and political ideas of the United States and Britain. As a systematically constructed language, Esperanto is democratic and transnational, not to mention easier to learn than idiomatic rivals.

The soul has a flock of flying eyes.

Close for a while, distant

for a while,

they descend and rise to the Only eye,

blue over

the horizon.

There is nothing stable in their wobbly wings

and the soul has always longed for stability.

—Daniel

Pastirčák (b. 1959)

Bratislava is a very new name for a very old city. The earliest

annals call her Brezalauspurc or Preslavaspurc, meaning Braslav’s

Castle, Braslav being a dux of East Francia. In the middle ages, as a

city under Hungarian and Austrian rule, this earlier description

transformed into Pressburg (Prešporok in Slovak, Posony in

Hungarian), by which it was known for most of its history. At least

two-thirds of Pressburg’s residents were ethnic Germans well into

the 20th century, and she did not become a majority Slovak city until

the Red Army sent the last Germans packing in 1945.

“Pressburg” was altogether too

German-sounding for a Slovak city, and the Slovak nationalist

movement cast widely about for a suitably native name for her.

“Bratislava” was invented in 1837, emerging out of a confused

etymology which took Bretislav I, King of Bohemia, as the eponym of

Brezalauspurc/Pressburg, rather than Braslav. Newly independent

Czechoslovakia nearly changed the name to Wilson City (Wilsonovo

mesto), in honor of the US President’s commitment to national

self-determination, before settling on Bratislava in 1919. (Wilson,

for his part, had to settle for dozens of Woodrow Wilson Avenues all

over the old Hapsburg dominions.)

Where are they, grandeur, power and

love? Their term

Was to have been forever, and the stream’s

ephemeral,

But they have passed and the white fount is here.

—Adam

Mickiewicz (1798-1855)

The diplomats had traveled far, from

Tokyo across the Russian Empire, when they came to Mukachevo,

carrying seedlings of the Japanese cherry tree as gifts to the

Emperor in Vienna. In the night when they slept, local thieves stole

several of the plants, and the next day sold them as fruit trees in

the markets of Uzhhorod. The trees, better known as sakura, do not

bear fruit, but by the time the Uzhhorodians realized it, they were

already captivated by the famously ephemeral beauty of the pale

blossoms.

This is but one of several stories

which tell how Japanese sakura came to grow so plentifully in

Uzhhorod, a city in the southwest of modern Ukraine, not far from the

Carpathians. More arrived in 2009, 2011, and 2017, as part of an

initiative of the Japanese embassy to plant over 1,600 sakura all

over the country. Every April more than a thousand sakura bloom in

Uzhhorod, more than any other city in Ukraine, and the magician Count

Sakura then marks the start of Uzhhorod’s Sakura Fest.

The Japanese empire once seeded its

Korean, Taiwanese, and Chinese possessions with sakura trees; today,

Japanese diplomats plant them alongside Ukrainian mayors. However,

the fact that sakura thrive in Uzhhorod means something very

different to the Japanese nationalist and the Uzhhorodian—for the

former it is a weapon in a soft power campaign; for the latter, it

has become the mark of a distinct and independent identity within

Ukraine, as much a symbol for this city as it ever was for Japan.

Gypsy melody that has haunted me,

Won’t you set me free of

all memory:

Of the time that’s wasted, of the path we traced

Of

the pain we taste—so endlessly!

—Yevhen Hrebinka (1812-1848)

Street performers have been a feature of every urban culture in

every corner of the globe. In Europe the tradition includes French

troubadours and jongleurs, German minnesingers, Russian skomorokh,

and Romani lăutari. The counterculture of the 1960s ushered in the

recognizably modern style of busking (a British term with a very

different meaning in Spain and France). Street musicians, playing

folk melodies or modern classics, are a common sight in Europe’s

town squares, cobblestone streets, and subway tunnels, where the

activity tends to bring in between 6 and 17 euros per hour. The

choice of a good pitch is essential, requiring pedestrian traffic,

visibility, and as little interference as possible.

Regulations vary widely, including no CD sales without a street

trading license (UK), no amplifiers (Switzerland), only three days in

thirty (Bruges), not on Saturdays or Sundays (Brussels), and not

between 12 and 2 in the afternoon (Austria). Some cities charge for a

busking license (Italy and southern France), others hand them out for

free or do not require one at all. The requirements of a pitch can be

opaque, and the city of London is perhaps the most complex mess of

differing bylaws, licensing schemes, permissions and prohibitions

depending on burough, park, square, and street.

Lviv locates its own tradition of street music with the batyar culture of the early twentieth century—a word meaning something

like “rascal,” derived from Hungarian betyár (“vagabond,

ruffian”) and Bulgarian bekjor (“bachelor, landless”), from

Turkish bekâr (“wifeless”) and Persian bīkār (“unemployed”).

The lighthearted love of bawdy songs, street slang, and practical

jokes, centered around Lychakivska Street, transcended the ethnic,

religious, and political affiliations of the multicultural city.

The king’s sharp sword lies clean and bright,

Prepared in foreign lands to fight:

Our ravens croak to have their fill,

The wolf howls from the distant hill.

Our brave king is to Russia gone,—

Braver than he on earth there’s none;

His sharp sword will carve many feast

To wolf and raven in the East.

—Bolverk Arnorsson (c. eleventh century)

The development of longship technology allowed Scandinavian peoples to take over the trade networks of Northern Europe at an opportune moment. The relative strength and urbanization of the Islamic world had created a strong demand for raw materials and labor, which were drawn from Europe to the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. Labor came most often as slaves, a commodity which the Scandinavians supplied by forging new routes from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Longships were light enough to be carried overland at portage points to the Volga and later the Dniepr Rivers, and Swedish rowers founded Novgorod and Kyiv as fortified trading posts along the way.

From the mid-ninth to the late-eleventh centuries, Scandinavian traders provided the bulk of slaves arriving in the Islamic world. Viking raiders captured slaves across the continent, but especially from the Slavic forest zones in the northeast, for markets on the Black Sea. Slavic peoples were so commonly sold that their name became synonymous with servitude: “sclavus” in Latin, “esclave” in early French, “sclave” in middle English, from which we get the modern word “slave.”

Slaves were Europe’s primary export in this period and yielded the highest return. Christian charity did not prevent Christian merchants from acting as intermediaries in these transactions, with major markets for European slaves in Rouen, Venice, and Dublin, where until 1170 the Irish sold captives taken in inter-clan wars.

Scandinavian merchant-princes exchanged slaves, amber, and arctic animal products for silver dirhams minted in Baghdad, silks from China and the Levant, tapestries from Constantinople, glassware from the Rhine, wine pressed from southern grapes, furniture, ceramics, and one mysterious statue of the Buddha, probably Gandharan in origin. Eager to to mark their success with personal ornamentation, Scandinavians garbed themselves in silk and in Muslim jewelry, which inspired later Nordic styles.

The early Rus continued to behave like their Norse forbears in conducting periodic raids on Constantinople by sea, often in order to secure better trading terms; they also adopted many of the customs, rituals, and forms of dress of the Turcoman tribes with whom they traded, especially when trade had been focused on the Volga River rather than the Dniepr.

The early Rus continued to behave like their Norse forbears in conducting periodic raids on Constantinople by sea, often in order to secure better trading terms; they also adopted many of the customs, rituals, and forms of dress of the Turcoman tribes with whom they traded, especially when trade had been focused on the Volga River rather than the Dniepr.

Dear God, calamity again! . . .

It was so peaceful, so serene;

We but began to break the chains

That bind our folk in slavery . . .

When halt! . . . Again the people’s blood

Is streaming! Like rapacious dogs

About a bone, the royal thugs

Are at each other’s throat again.

—Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861)

When Gerhardt Friedrich Müller first introduced to the Russian Academy of Sciences his theory that the Russian state began when the disorganized and bickering Slavs invited a Swedish viking dynasty to rule them—“glorious Scandinavians conquered all the Russian lands with their victorious arms!”—the uproar which ensued forced the German to cut short his lecture, and in the end to burn the paper it was written on.

The origin of the Kievan Rus remains a matter of controversy among historians, with heady implications for Ukrainian and Russian nationalism. Even the world “Rus” is possibly derived from a Norse word for “rowers.” Slavic historians mostly reject a very direct reference to viking rule in the Russian Primary Chronicle, a reference born out by Byzantine sources and archaeological evidence, because it implies that their ancestors needed outside help to organize a state. If the Chronicle and Müller’s theory are true, then the rise of Kiev was not “the exclusive achievement of one ethnic group” but the result of a complex and geographically broad interaction. For nationalists, that sort of interaction is simply incomprehensible. (They have not, as yet, produced a successful alternative explanation.)

In this sort of disagreement, evidence is embraced or it is burned depending not on its accuracy but on its suitability to a preexisting national mythology, which is fixed and sacrosanct. This is an all too familiar story.

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

—William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Grand Prince Vladimir began his life as a great barbarian, “wily, voluptuous, and bloody.” He secured the throne of Kiev by the murder of his brother and by marriage to five women (who, in addition to his 800 concubines, earned him the nickname fornicator maximus), but this did little to legitimize or institutionalize his power. Neither Norse nor Slavic paganism were up to that task, and so he turned to foreign religions.

From the Volga Bulgars he learned of Islam, though the requirement of circumcision and the taboo against alcohol made him quail equally—“Drinking is the joy of all Rus’. We cannot exist without that pleasure.” From the Khazar horsemen he learned of Judaism, though a people who had lost their homeland had clearly been abandoned by their god. The churches and rituals of the Germans and Poles did not impress his emissaries.

His deputies to Constantinople, however, returned in awe. “We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth,” they said, describing a liturgy in the Hagia Sophia, the power of the religious songs, the brilliance of the priestly vestments, the magnificence of the ceremonies and of the Emperor.

Close contact between the Norse and Byzantine world perhaps already inclined Vladimir to choose the Byzantine religion, but so did the pre-Christian expectation that proper worship bring protection and power. The peoples of the Kievan Rus preferred to imagine the Christian God as the Lord of hosts, with the power to deliver plagues to Egypt and victory to the righteous kings of Israel, a power which manifested itself in the grandeur of Constantinople.

Vladimir’s proposal to marry Emperor Basil II’s sister Anna shocked the court and horrified the princess. Nonetheless, with the formal conversion of the pagan prince, a marital alliance was concluded, pagan monuments destroyed, churches and monasteries erected, and the people of the Rus’ baptized. (He had somewhat more trouble setting aside his concubines.) The conversion of Saint Vladimir was an important event in the emergence of a Russian identity in the eleventh century, as the Kievan court adopted Slavic customs and the Slavonic language and brought Roman civic and Orthodox ecclesiastical institutions from Constantinople to the forest zones of Eastern Europe.

Beat the squares with the tramp of rebels!

Higher, rangers of haughty heads!

We’ll wash the world with a second deluge,

Now’s the hour whose coming it dreads.

—Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930)

The largest Soviet monument in Rzeszów is called the Great C*nt. The mere sight of it will tell you why, dear Reader, but I assure you: the story is more interesting.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the mass-produced art of its public spaces became obsolete. Revolutionary movements and newly-independent governments demolished statues of Lenin, et. all, in scores, or else removed them to bizarre sculpture gardens, such as Grutas Parkas in Lithuania (advertised to tourists as “Stalin World”) and Szoborpark outside Budapest. On uncounted pedestals, national heroes—generals, scientists, poets, and mythic warriors—have pushed aside party leaders, and it is now almost impossible to find the once omnipresent hammer-and-sickle anywhere outside Russia. This iconoclastic will remains, though the Russian Federation often exerts pressure to block the relocation of Soviet monuments, in particular those honoring the sacrifices of the Great Patriotic War.

For remaining edifices, the only active solutions are vandalism (see that famous Red Army monument in Sofia) or recontextualization. Take, for instance, the colossal Monument of the Revolutionary Deed, unveiled on May Day 1974 and towering still over a central roundabout in Rzeszów in southeast Poland, despite the sale of its grounds to the Bernardine Order in 2016 with plans to remove it. The central scene—a typical one of brave peasants and workers leaning forward with the motion of progress and the inertia of square jaws—is set in a pair of high, parenthetical stones, suggesting to some a rabbit’s ears, christened by others Wielka Cipa, the “Great C*nt.”

Today this vulgar association is so strong that hardly anyone remembers the real name, but ask a local where to find Wielka Cipa and he or she won’t even blush.

Hail, O Christ, Thou Lord of Men!

Poland in Thy footsteps treading

Like Thee suffers, at Thy bidding

Like Thee, too, shall rise again.

—Kazimierz Brodziński (1791-1835)

“The Polish national movement had the longest pedigree, the best credentials, the greatest determination, the worst press, and the least success,” wrote Poland’s best known historian. It birthed an uprising every generation between the First Partition and the Second World War—in 1733, 1768, 1794, 1830, 1848, 1863, 1905, 1919, and 1944 (not counting the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943).

Though ending in defeat, though “forgotten by the world” in a poem by Czeslaw Milosz, the legacy of this heroic struggle has galvanized Polish national identity. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Warsaw. Three times it was destroyed, always in summer, always “under such suns, heat, burning, planes.” The invasion of September 1939 leveled an eighth of the city, the ghetto uprising from 19 April to 20 May 1943 left Muranów a charnelhouse, and the 1944 Warsaw Uprising reduced the remainder of the city to rubble.

“Warsaw was betraying all her secrets,” wrote Miron Bialoszewski in his Memoir—“Everything was exposed. From top to bottom. From the Mazovian princes. Up to us. And back again. . . . Our kings were not protecting us. Nor were we protecting our kings. Nor what had come after them. Everything. Everything.” Was this a failure? No, it was a sacrifice, a resurrection!

“I wanted Warsaw to be a great city,” said her mayor, Stefan Starzyński, five days before her capitulation—“I see it now from my window in all its grandeur and all its glory, enveloped in billowing smoke, glowing red from the flames, magnificent, indomitable, great, fighting Warsaw. Where we had envisaged wonderful orphanages, there is rubble. Where we had planned parks, today there are barricades thickly strewn with corpses . . . yet it is not fifty, not one hundred years hence, but today, as it stands in defense of Poland’s honor, that Warsaw stands at the summit of its greatness and its glory.”

Here in America you can take

as much land as you need.

You

do what you like.

Nobody watches you. . . .

—Wincenty Witos

(1874-1945)

At the end of the nineteenth century, around four million Poles,

from a total population of 20 to 25 million, left. Some went at first

to Prussian estates for a summer of agricultural work, or to Saxony

or Silesia for a season in a factory, but later, as Poles migrated to

the USA, Brazil, Argentina, and Ottoman Syria, the pattern of

seasonal migration extended from a season to a career to a lifetime.

What drove Poles from Poland? There was rural overpopulation and

urban poverty—just as in the other major sources of European

emigration, Ireland, Sicily, and Germany—which compelled the poor

to turn their back on the homeland and seek a new life in slums

abroad. Political and religious persecution, including the

Kulturkampf of Kaiser Wilhelm and the pogroms of the Russian Tsars,

forced the educated urban elite to take refuge under other flags.

Although many intended to return, few could.

The arrival of the former in the US coincided with the growth of

industrial towns in the Midwest and Northeast, hence the continuing

concentration in Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo,

Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Others moved on from the

cities to the kind of agricultural life idealized then as now by all

those oppressed by urban realities—to Warsaw, Alabama, and

Kosciuszko, Mississippi, and Pulaski, Texas. Like all immigrants,

Polish-Americans have contributed much to American prosperity: drawn

from four percent of the US population, they accounted for 17 percent

of enlisted men in the Second World War.

Today there are 20 million people of Polish ancestry living

abroad, compared to 37 million people living in Poland itself. Look

back at old Gdynia (the port of Gdansk, called Danzig in German) and

there they began, just as in Hamburg and Riga, on their way to Ellis

Island or Buenos Aires: Poles of all sorts, not just speaking Polish

but German and Ukrainian and Yiddish, not just Catholics but Poles

practicing Judaism and the Eastern Catholic rite, often organized

under a priest or rabbi, hoping and dreaming for a better life

somewhere out there.

America, I sing back. Sing back what sung you in.

Sing back the moment you cherished breath.

Sing you home into yourself and back to reason.

[...]

When my song sings aloud again. When I call her back to cradle.

Call her to peer into waters, to behold herself in dark and light,

day and night, call her to sing along, call her to mature, to envision—

Then, she will make herself over. My song will make it so

When she grows far past her self-considered purpose,

I will sing her back, sing her back. I will sing. Oh, I will—I do.

America, I sing back. Sing back what sung you in.

—Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, 2014

In his “Symphony from the New World,” Antonín Dvořák flies from the misty horizons and rolling birch-strewn hills of Bohemia to the land promised by world’s first Constitution, the land promised to those without power and those without a voice. There, a son of Bohemia, a son of a peasant father who dreamed that his son would be a butcher, became instead the director of the Conservatory of Music in New York. There he premiered his most famous symphony in Carnegie Hall in December 1893.

Dvořák insisted that the future of American music must be founded in the music of African and indigenous people living there, just as he took his own inspiration from the Slavonic folk traditions. “These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

His Symphony represents, in the words of one critic, “a hopefulness without frontiers which, paradoxically, is welcoming because centered on an idea of home.” A home without boundaries. “A utopian paradox.”

Art:

ReplyDelete“Constitution of May 3, 1791” (1891) by Jan Matejo.

“Reception of the Jews” (1889) by Jan Matejko.

“Ritual Murder” (18th century) by Charles de Prevot. The painting, mounted on a wall of the Sandomierz Cathedral, was hidden behind a curtain from 2006 to 2014.

“Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God” (1873) by Jan Matejko.

Photograph of the Wawel Cathedral (2018).

A stamp from the Pilsner Urquell Brewer in Plzen, “A half liter in one sip.”

Still from “Der Golem” (1915), written and directed by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen.

“The Leshy” (1906) by P. Dobrinin.

Portrait of L. L. Zamenhof.

Photograph of Bratislava (2018).

Photograph of a tree in bloom by the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Uzhhorod (2018).

“Gypsy Dance” (19th century) by Richard Lipps.

“Guests From Overseas” (1901) by Nicholas Roerich.

“Wielka Cipa” by Jarosław Ejsymont. The speech bubble reads,

“Have you ever been to Rzeszów kitten?”

AP photo from September 1939 of a young Polish boy among the ruins of his home during a pause in German air raids on Warsaw.

Photograph of the M.S. Batory in New York. The Batory went into service in May 1936 ferrying migrants across the Atlantic on the Gdynia to New York route. Her exploits during the Second World War, ferrying troops, supplies, and refugees around and away from the European Theater, earned her the nickname “The Lucky Ship.” She continued to transport emigrants from 1951 to 1971.