Letters from the Silk Road

Central Asia has always held out to me a special enchantment. There at the Jaxartes ended the empire of Alexander; there in the trackless steppe gathered the hordes which plagued the ancient and medieval world; there on dusty plains lie Samarkand, Kashgar, and a scattered constellation of cities where the meandering trade roads between East and West converge.

The term “Silk Road,” though not coined until 1877, announces an older half-imagined adventure of camel trains in haunted wastes, of turbaned merchants in covered bazaars, of danger and romance by starlight. Archaeological evidence suggests that commerce between China and Europe never matched the vision of orientalists. Nevertheless, the transcontinental route that we call the Silk Road changed history by transporting and transforming the culture, religion, art, and technology of every civilization it touched.

My own journey along Silk Road—from a ferry embarked in Kobe harbor on 10 May to a final flight from Madrid on 9 September—was overland by pilgrim need. “For the lust of knowing what should not be known,” I wanted to see the gradual change of the world, in all its physical, social, and spiritual dimensions, and to that end I traveled by a series of boats, trains, and buses through China, Central Asia, Russia, and Europe, marking down along the way all that I could see of a world without borders.

In singing-girl towers to play at dice, a million on one throw;

By flag-flown pavilions, calling for wine, ten thousand a cask.The Mayor? The Governor? We don’t even know their names:

What’s it to us who wields power in the palace?

―Lu You (1125-1209)

Shanghai, on the lower jaw of the Yangtze, has supplanted all other ports on that historic river―and nearly every other city on earth―in size, wealth, and mercantile vitality, ever since the Western powers forced concessions here in the wake of the First Opium War (1839-42). Until a few centuries ago, all seagoing Silk Road trade embarked from the Yangtze (the Yellow River was unnavigable), by way of Hangzhou or Nanjing, on its way south to Malaya, India, Persia, and Arabia.

Like an ancient ruin, the grass grows high: gone are the guards and the gatekeepers.

Fallen towers and crumbling palaces desolate my soul.Under the eaves of the long-ago hall fly in and out the swallows

But within: Silence. The chatter of cock and hen parrots is heard no more.

—Xie Ao (1245-1295)

Beijing had little place on the Silk Road until the coming of the Mongols, when Kublai Khan made this the capital of China, and when other heirs of Genghis ruled Central and Western Asia. Once more merchants (including Marco Polo) could travel in safety the innumerable desert tracts, mountain passes, and oasis towns that stitched together East and West, as had not been possible since the early Tang Dynasty (618-755). This cross-continental trade more or less ended with Kublai’s Yuan dynasty (1271-1388). The Silk Road reverted to what it has almost always been―a market for small-scale peddlers of locally-produced commodities―while Europeans began searching for their own route to Asia.

I would cross the Yellow River, but ice chokes the ferry.

I would climb the Taihang Mountains, but the sky is blind with snow.

I would sit and poise a fishing pole, lazy by a brook—

But I suddenly dream of riding a boat, sailing for the sun . . .

Journeying is hard,

Journeying is hard.

There are many turnings—

Which am I to follow? . . .

I will mount a long wind some day and break the heavy waves

And set my cloudy sail straight and bridge the deep, deep sea.

—Li Bai (701-762)

Travel on the Silk Road was never easy. Envoys, monks, and merchants spent months to prepare for every week-long stage―gathering information, planning a route, bartering for fresh pack animals, hiring guides and maybe guards. They waited for warmer weather to open the icy passes of the Pamirs, or for cooler weather to allow passage through the Taklamakan Desert in Western China. My own trip is not so difficult; each twelve-hour journey by train is preceded by a few days of rest and sightseeing. Nonetheless, the eight days spent in Beijing, waiting for a visa, are thankfully over.

Chang’an lies in mournful stillness: what does it now contain?

—Ruined markets and desolate streets, in which ears of wheat are sprouting.

Fuel-gatherers have hacked down every flowering plant in the Apricot Gardens,

Builders of barricades have destroyed the willows along the Imperial Canal.

All the gaily-colored chariots with their ornamented wheels are scattered and gone.

Of the stately mansions with their vermilion gates less than half remain.

The Hanyuan Hall is the haunt of foxes and hares.

The approach to the Flower-calyx Belvedere is a mass of brambles and thorns.

All the pomp and magnificence of the older days are buried and passed away;

Only a dreary waste meets the eye; the old familiar objects are no more.

—Wei Zhuang (836-910)

Cultural preservation in China has taken a backseat to material progress. From below there is a demand for the symbols of modernity in steel and glass, an association of the classic with the primitive. From above there is a drive to make straight and wide the winding alley, to impose control and efficiency, to maximize profit. Historic buildings and neighborhoods have been steadily demolished since the 1950s, with occasional sprees. Beijing razed and rebuilt a third of its core in preparation for the 2008 Olympics—rows of cookie-cutter concrete over the ruins of charming hutongs, slate boxes in place of white houses with stone-tiled roofs, a phone directory instead of a community. Although the fashionable Xintiandi neighborhood in Shanghai has shown how preservation and profit can go hand-in-hand, by evicting families to make way for Starbucks, homes there were more often rebuilt than put through costly renovations.

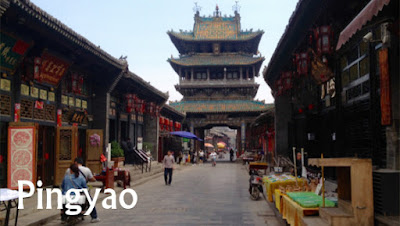

Travelers who wish to see a Chinese market town as it once was can visit Pingyao in the north (or Lijiang in the southwest); the towered walls and narrow lanes preserve the husk of five centuries of history, but the main streets are all turned over to vendors of cheap knickknacks and fake antiquities. Only a few people live there anymore, like spiders in a museum.

Green mountains range beyond the northern wall.

White water rushes round the eastern town.

Right here is where, alone and restless, he

Begins a journey of a thousand miles.

While travelers’ intents are fleeting clouds,

A friend’s affection is setting sun.

He waves goodbye, as he goes from here.

His dappled horse lets out a lonely neigh.

—Li Bai (701-762)

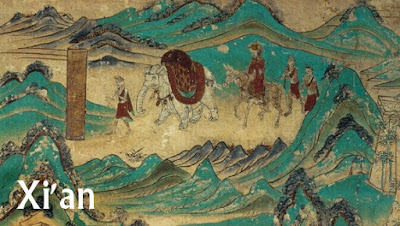

Six hundred years before Marco Polo, the storied monk Xuanzang (602-664) set out from China to India. He slipped past the border despite a ban on travel, nearly died in the desert, was robbed of all his possessions including his clothes, received aid from the King of Turfan, the Khan of the Gokturks, and the Shah of Samarkand, and visited every corner of India before returning home, seventeen years after his journey began. Xuanzang brought 1330 buddhist texts with him to Chang’an, modern Xi’an, capital of ten dynasties including the Tang. He persuaded the emperor to build the Big Goose Pagoda to store them, and he spent the next nineteen years producing translations. His twelve volume account of his travels covers the 110 cities and states he saw himself, as well as dozens more known by hearsay, and inspired the beloved novel Journey to the West.

Despite the popular image of merchant caravans, the most common traveler on the Silk Road was probably the monk. Monks acted as envoys of the state. They made pilgrimages to Mount Wutai or the stupas of Central and South Asia. Scholars like Fuxian, Xuanzang, and Ennin traveled to learn from the libraries of Chang’an, Nalanda, or Ceylon. Often a monk had all three roles in mind (as I have at least two). Textual evidence like the Book of Zambasta illustrates the cosmopolitan role of monks by anthologizing texts from Sanskrit, Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Tokharian, and Uighur.

The Silk Road represents not only or even primarily an exchange of commercial goods, but of culture, language, religion, art, and technology. Buddhism came to the north, Islam to the south, paper to the west, astronomical innovations to the east; and it was in this that world history was changed.

From the West he was born,

He received the Holy Scripture,

A Book of thirty parts,

To guide all creation,

Master of all Rulers,

Leader of Holy Ones,

With Support from Above,

To Protect His Nation,

With five daily prayers,

Silently hoping for peace,

His heart towards Allah,

Empowering the poor,

Saving them from calamity,

Seeing through the darkness,

Pulling souls and spirits,

Away from all wrongdoings,

A Mercy to the Worlds,

Traversing the ancient majestic path,

Vanquishing away all evil,

His Religion Pure and True,

Muhammad,

The Noble & Great one.

—The Hongwu Emperor (1328-1398)

The Silk Road was a conduit for religion. Buddhism entered China from India, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism from Iran, and the Christian Church of the East (often called “Nestorianism”) from Syria, coexisting with each other and with the native traditions of their new home.

Ethnically Chinese Muslims, descended from Arab, Persian, and Turkish traders who intermarried with local people, are today called the Hui. Their communities are spread across China, from Lhasa to Beijing. In Lanzhou, on a crossing of the Yellow River just north of the “Mecca of China” in Linxia, one in twelve are Muslim Hui. Many of their mosques and pagoda minarets would be indistinguishable from the neighboring temples if not for the Arabic inscribed in stone, the white caps and colorful headscarves of the faithful.

The Hui acknowledge their place in the Chinese nation and consent to its politics (the “good Muslims” we hear so much about today). As a result they enjoy largely unrestricted rights to observe Ramadan, make the Hajj, and wear the veil—unlike the more independent Uighur of Xinjiang.

A passerby at the roadside asks a conscript why.

The conscript answers that drafting happens often. . . .

‘At the frontier posts, the blood we shed becomes a sea,

And the war-loving emperor dreams of conquest without end.’

―Du Fu (712-770)

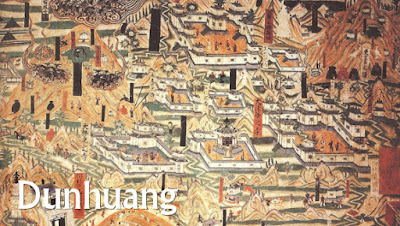

Dunhuang is the last in a string of oasis towns called the Gansu Corridor, leading west from Lanzhou to the Tarim Basin. Traders, travellers, and armies all followed this strip of habitable land between the Gobi Desert to the north and the Kunlun Mountains of Tibet to the south. Buddhist pilgrims came to the nearby Magao Grottoes, and generals, soldiers, and spies of the frontier sponsored many of the elaborately painted caves (like the one above).

Silk came to the Silk Road more often through the garrisons of the Han and Tang empires than by the long-distance merchant caravans we tend to imagine. Government officials brought silk west to pay soldiers and buy supplies, and officers used it to trade for the renowned horses of Central Asia. Bolts of silk―undyed, simply patterned, cut to a standard size―were lighter than bronze coins and lasted longer than grain.

When the Tang empire first spread into modern Xinjiang, trade flourished along the Silk Road. When they withdrew from the western frontier in the eighth century, the flow of silk, coins, grain, and men into the oasis towns ceased, and the Silk Road reverted to a small-scale, local, barter economy.

Fire-wagons! One had heard of them . . .

these wagons, chained one to the other and drawn

neither by man nor beast, but by a machine

breathing forth fire and water like a dragon.

—Sai Zhenzhu (1892-1973)

From Dunhuang, travelers of the Silk Road chose one of two ways around the arid wastes of the Taklamakan. The southern route, which treads the Kunlun foothills, was largely abandoned in the sixth century. The northern route follows the Tian Shan and Tarim River through Turfan, Yanqi, Kuqa, and Aksu to Kashgar. This became the ineptly named Southern Xinjiang Railway Line, completed in 1999, thus connecting the northern route to points as far removed as Saigon and Seville.

“The railway bazaar,” wrote Paul Theroux, “with its gadgets and passengers, represented the society so completely that to board it was to be challenged by the national character.” In China, these gadgets begin with a water heater at the end of every car and a tall metal thermos in every booth, to prepare tea and instant noodles. Stewards range the narrow aisles with baskets, which they use to carry plastic-wrapped processed snacks and to bludgeon the knees of passengers. The cars come in soft and hard class, an ostensibly classless distinction inherited from the Soviet lexicon.

No matter where one sits or sleeps, one hears the slurp of noodles and the crack of sunflower seeds, the clipped vowels of Chinese chatter, the battle cries and the hiss of arrows from a drama played at full volume over tinny speakers (few people bother with earbuds), and above it all the constant drone of the railway intercom, with forcefully-delivered advertisements interspersed by safety announcements and pop songs. This goes on until 11 pm, when the lights go abruptly black, leaving a nebula of screens aglow in the rattling gloom.

A long while ago now

in those chipped years like a camel’s tail

in those dim months like a desert mirage

in those unchanging days blurring into each other

everyone was brought head first into this world

The golden oleaster flowers and the

copper grains of sand smelled like an upset stomach

Ugly people with no concern for their own souls

would lock winter in spring and insult it left and right

It was then that crawling water was discovered

Everyone’s left eyelid would quiver in the morning

and they’d tell each other, may God take pity on you

One who stole fruit or books or wives was not a thief

The world made no promises to anyone

The angel of death didn’t neglect a single elder

Men looked to women’s feet, women to men’s hands

God stayed up nights pairing off men and women who looked like each other

Children were born merely because men and women got married

When children asked, When will we be grown up

Their mothers said, When the sun shines on a Thursday

When youths asked, When will we be happy

Their elders said, when a camel tail touches the earth

The sun never shone on a Thursday, a camel tail never touched the earth

In each person’s home was an old stove

with a flame no one dared to extinguish

In each person’s courtyard was a dark well

no one had the courage to uncover

In each person’s heart was a strange hope

no one was willing to speak aloud

It was a time like that

and it often resumes even now

—Tahir Hamut (b. 1969)

The city of Turfan sits in a depression of the Tian Shan. It is the lowest point on earth after the Dead Sea and the hottest place in China bar none―42° (108°F) during my stay in late spring. Old Turfan's Chinese residents, who fled the violence of the Three Kingdoms period to this peaceful oasis of cotton trees and grapevines, called it Hozhou (火州), the prefecture of fire; these Chinese refugees were so numerous that the Soghdian traders called it Chinatown. Today, Laocheng Road divides the brand stores and garden cafés of the Han Chinese from the Uighurs’ mazy bazaar and that other world of old dun-colored neighborhoods.

We came down on them like a flood,

We went out among their cities,

We tore down the idol-temples,

We shat on the Buddha’s head!

—Mahmud al-Kashgari (d. 1102)

Human travelers cannot long survive the wastes of the Tarim Basin, but the things they leave behind him last for millennia under the sands. The old Silk Road is a modern treasure trove of painted frescoes, clay structures, leather goods, cloth and clothing, and documents, from shopping lists to tax receipts to Manichaean liturgies, which could not have survived anywhere else.

Man is not so merciful. Archaeologists sometimes damage the fragile relics they seek to study or remove, and development often occurs at the expense of preservation. However, the demolition of Silk Road cities by the Chinese authorities was a deliberate cultural holocaust.

In Kashgar, 85 percent of the historic city center was obliterated and replaced: warrens of centuries-old mosques, markets, and houses crushed beneath stucco facsimiles or Chinese apartments. Communities of the restless Uighur, the Turkic-speaking majority in Xinjiang, gave way to the Chinese migrants who manned the wrecking balls. Construction displaced 200,000 in Urumqi alone. In some cases, neighborhoods were leveled and then left as dusty fields―the abomination of desolation.

At just that moment

I was eyemate to a blind one

and went among you

You must have thought we couldn’t see

Some of you said you’d show us the house of God,

then led us to dwellings you’re still building after centuries

We didn’t mind

Some of you without a second thought

told us your diaries and wives

were your sacred customs

We didn’t mind

Some of you claimed to speak of love

and untied the knots concerning your bodies

and tried to pin upon us the flowers that grew there

We didn’t mind

Saying, ‘This is our writing,’

you laid books upon the table

and entered us into them

we two blind ones looked, but

pictures hanging crooked on yellow walls

prophets seeking water among the pictures

angels on cliffs, holding up the heavens

fair girls drinking love in burnt nests

fishes ready to turn into the sky

monks whose wine craving comes from the ocean

None of them were there

We didn’t mind

Some of you walked holding your fate,

and shocked to find our fate had fallen

you grandly gave us the one in your hands

We wore your fate

we fell to flames and burned it

. . . we didn’t mind

But there was one thing none of you would give

In the box of your souls

there was a black jar

and we had the key to that jar

it was in our blind eyes

We spoke of that jar

you said we were blind

and saying, ‘We never had such a jar,

you’re no travelers, you’re wounds that never heal

you’re no people, you’re Satanic fragments

you’re not really blind, you’re thieves, you’re ravens that break the peace,’

you drove us away

We didn’t mind

It’s true we have no love, no curses either

It’s true we have no tradition, no breaking either

It’s true we have no fate, no blindness either

For all that, we didn’t mind

But what seemed so curious

at just that moment

was that our eyes could see . . .

—Osmanjan Muhemmed Pas’an (b. 1981)

The Tarim Basin is a node of Asian peoples—Indo-European nomads migrated here from the Ukrainian steppe; refugees swept in from the war-torn Punjab, from conquered Iran and the collapsed empires of China; traders arrived from Samarkand and Xi’an, soldiers from Mongolia and Tibet; monks traveled between holy places across every horizon; conquerors from Transoxiania brought Islam; Sufi saints made it stick. Populations were not displaced but intermixed, and linguistic change was the norm.

The Uighurs came to the Tarim Basin in the ninth century from the grasslands of modern Mongolia. Their Turkic tongue became the language government and trade, while Islam gradually replaced the Buddhism and Manichaeism of their ancestors to become the dominant religion in modern Xinjiang (the Chinese name of the western region, which means “New Frontier”).

Today’s Uighurs reflect the region’s multicultural heritage. “There is no Kashgar type,” as one European visitor put it in the early twentieth century. “Some could be Mongolian, some could be Czech,” said a twenty-first century traveller from Prague, and one might add Indian, Iranian, or Turkish—dark or pale, black-haired or blonde. They carry the legacy of the Silk Road in eyes blue, grey, brown, and black.

Where’s the trail to Cold Mountain?

Cold Mountain? There’s no clear way.

Ice, in summer, is still frozen.

Bright sun shines through thick fog.

You won’t get there following me.

Your heart and mine are not the same.

If your heart was like mine,

You’d have made it, and be there!

—Hanshan (c. 730-850?)

Tashkurgan is an ancient trading post with a Scythian name, set in the midst of the Pamirs. Asia’s largest mountain ranges—the Tianshan, Kunlun, Himalayas, and Hindu Kush—are tied up here in a node of icy crags, treacherous passes, and desolate plateaus at the heart of the continent.

This Pamir Knot was a major hurdle on the Silk Road; once through, the traveler was free to continue south to the Indian subcontinent (today via the Karakoram Highway to Pakistan and the Chinese port at Gwadar) or west into the Ferghana Valley. The spies of the British Raj recorded the local name as Bam-i-Dunya, the Roof of the World.

On a mountain side in the wide Altay,

While the Kyrgyz were in distress,

After the passage of many days and nights,

After the passage of summer into mid-autumn,

When the animals were fat, ...

A lion arrived, whom we so long awaited.

He was born with rage in his hands.

He shouted while still in the womb

And called out the battle cry ‘Manas!’

Among the gray, pale-headed sheep.

—Epic of Manas

Every spring, Kyrgyz families pack their yurts on top of an old cart or an even older Russian Lada and return to the jailoos, the summer pastures. There, in alpine valleys made green by the snowmelt of the Pamir Alay, Tian Shan, Kokshal, and Alatoo, they revert to semi-nomadic pastoralism, with only small material differences from that of the millennia preceding Soviet collectivization. They tend the herds of horse, cattle, sheep, and goats, make fresh butter and fermented mare’s milk (kymys), and enjoy an altogether more wholesome and freer living than can be found in the “developed” cities.

Helmets and swords, with curious art they made,

Guided by Jamshid’s skill; and silks and linen

And robes of fur and ermine. Desert lands

Were cultivated; and wherever stream

Or rivulet wandered, and the soil was good,

He fixed the dwellings of his people.

—Abolqasem Ferdowsi (c. 940-1020)

All silk begins as the small ovoid cocoon of the silkworm. These cocoons are stirred in hot water to degum and free the silk filament, drawing as much as a mile from each. The filament is then wound on a reel into thread, and the thread dyed and woven on a loom into the cloth itself. A single pound of silk requires around 2,500 cocoons; a single scarf takes hundreds.

Silk production began in China, which maintained a monopoly on sericulture until the first millennium AD. One legend tells of the Khotanese princess who smuggled a silkworm from China to Turkestan, but silkmaking most likely spread the same way as other technologies: through trade along the Silk Road.

The Yodgorlik Silk Factory in Margilan is one of the few places where silk products are still made by hand in the more-or-less traditional way.

My roaming was not of my choice; nor could I decide whether to go or stay.

Nor power to stay was mine, nor strength to part;

I became what you made of me, oh thief of my heart.

—Babur (1483-1530)

If you look on a political map at the jigsaw puzzle where Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan meet, you would never suspect the Ferghana Valley. The landscape, so wide that neither the northern nor the southern hills can be seen from the central line, is lush with melon fields, fruit orchards, and cotton plantations. The cities of Osh, Andijon, Kokand, and Khujand are among the region’s largest, oldest, and most historically significant.

The integrity of the Ferghana Valley was intentionally disrupted by Soviet planners, Stalin in particular, when they carved up the region between 1924 and 1936. Osh, a majority Uzbek city, became part of the Kyrgyz Republic. The western gates at Khujand became Tajik. The rest of the valley went to Uzbekistan, which meant that access between Ferghana and the capital depends on a pair of vital tunnels through the Tian Shan.

Divide and rule continues to bear bloody fruit: ethnic revolts in Osh (1990, 2010), a massacre in Andijon (2005), and enduring friction between Tajiks and Uzbeks.

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth!

—Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

In 1865 the Russian Empire captured Tashkent, an ancient city of Transoxiana and the first of many Central Asian conquests to come. The British feared that Russian Cossacks would sweep down on India through the northern passes as so many invaders had before. This began another round of the Great Game, which the Russians called the “tournament of shadows,” when agents of both sides, disguised as horse traders or pilgrims, faced death and worse to map the trackless and lawless regions between their empires and to secure commercial and strategic arrangements with Shahs, Amirs, Khans, and tribal Chiefs along the old Silk Road.

Today a new Great Game is played over the same terrain, in what was until 1991 called Soviet Central Asia. The stakes are not only strategic and political but material, including untapped reserves of oil and gas, as well as gold, silver, copper, zinc, lead, and iron. Oil pipelines have replaced caravan routes as the arteries of the continent. The list of players has expanded to include the USA, awakened China, eastward-facing Turkey, independent India and Pakistan, and a lineup of multinational corporations. And names like Uzbekistan, with its capital in Tashkent, appear in the news often enough to force even the most insular to try pronouncing them.

We travel not for trafficking alone,

By hotter winds our fiery hearts are fanned.

For the lust of knowing what should not be known

We take the Golden Road to Samarkand.

—James Elroy Flecker (1884-1915)

“Everything I heard about Samarkand is true,” Alexander of Macedon is reputed to have said, “except that it’s more beautiful than I ever imagined.” Samarkand has always been an object of Western fascination, “the gem of the Orient,” the name which more than any other summons the magnificence, mystery, danger, and romance of the East.

Samarkand is a synonym for mighty Asiatic empires in Marlowe and Milton and Poe, for the danger of imperial adventurism in Wilde, and for luxury and splendor in Keats. Here Omar Khayyam penned his Rubaiyat, his ode to earthly pleasures, which later became an epicurean manifesto in the English adaptation by Edward FitzGerald. Samarkand is the home of Prince Calaf in Gozzi and Schiller’s Turandot operas, and the setting for many of the Thousand and One Nights Entertainment. The city was a keynote for Victorian travelogues by Alexander Burnes, Arminius Vambery, and Lord Curzon, later Viceroy of India, who called it “the wonder of the Asiatic continent.” Artists of the Russian Empire painted it as if this were so.

Everything you hear about Samarkand is now too wild to be true. The last words on the subject belong to Hafez, who wrote with less exoticism and infinitely more romance that he would sell Samarkand, and Bukhara too, for the black mole of a girl he loved.

I looked for God.

I went to the temple, and I didn’t find Him there.

Then I went to a church, and I didn’t find Him there.

And then I went to a mosque, and I didn’t find Him there.

And then finally I looked in my heart, and there He was.

—Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207-1273)

The turquoise domes, monumental gates, and delicate tilework of Central Asian architecture are a lasting tribute to the complexity of the region’s artistic heritage. The oldest buildings belong to the Greeks, Persians, Scythians, and Turks, whose empires crossed steppe and desert, but the most famous are those of Tamurlane (d. 1405) and his heirs and followers.

Tamurlane, a local bully who conquered the world, brought artisans from all over his empire to the capital in Samarkand, resulting in an eclectic syncretism. Signatures include the use of glazed blue tiles, the grand outer dome and massive entrance portal (pishtak). Islamic law forbids the artistic representation of human or animal form, and yet medieval decorations here as often includes the lion, peacock, and simurgh as the more conventional flowery pattern and Quranic quotation.

The environment also had its say. The lack of wood and stone compelled the use of fired brick and glazed tile in the cities of the plain. The massive gateways’ inward slope caught the wind and allowed air to circulate through guarded courtyards. Low doorways trapped heat in the winter, and high domed ceilings invited the cool air on summer nights.

Men could be more than they are, if they would try for it. He has shown them that. How many have tried, because of him? Not only those I have seen; there will be men to come. Those who look in mankind only for their own littleness, and make them believe in that, kill more than he ever will in all his wars.

—Mary Renault (1905-1983)

Alexander the Great!—still he keeps his immortality, and here, in a far dusty spot at the edge of the Kyzylkum desert, one hour by shared taxi from the nearest railway stop, he is remembered daily as Aleksandr Makedonski, builder of that fort which towers over the modern town and draws a few pilgrims from the nearby mosque.

The ruins at modern Nurata was one in a line of forts constructed along the Jaxartes River (modern Syr Darya). Alexander looked north from here at the Scythian sea of grass. He knew that shortly beyond this lay the World Stream of Ocean, which encircled Europe, Libya, and Asia, in which the Caspian was only a gulf. His geography was incomplete.

Alexander’s contemporaries, like many of ours, did not realize the full breadth of Africa and Asia. Unfortunately, despite the ubiquity of satellite maps, general knowledge of geography has seen small progress from two millennia ago. Regions which took an Alexander to reach are today accessible by budget airline, yet how few are ready to pay the ticket price!

“Where does wisdom dwell?”

“Nowhere, O king.”

“Then there is no wisdom.”

“Where does the wind dwell?”

“Nowhere.”

“Then there is no wind!”

“You are dexterous, Nāgasena, in reply.”

—Milinda Panha (2nd cen.)

The kingdom of Bactria was an outpost of the Hellenistic world at the eastern periphery of the empire Alexander had won with the spear, 3000 miles from Greece. The region of modern Afghanistan was as difficult to conquer then as it is now, and thousands of Greek and Macedonian soldiers were settled there in garrison towns. Here as nowhere else the cultural fusion envisioned by Alexander was realized, mostly due to its geographic isolation.

Evidence is scarce, but numismatics (study of coins) have been supplemented by recent archaeological efforts by the French team at Aï Khānum in Afghanistan, once called Alexandria-on-the-Oxus. It was as if a Greek town had been transplanted to Central Asia, complete with a gymnasium and theater, dolphin-shaped fountains, and Greek-style villas with mosaic floors. A palace complex centered the town, its columns topped with Corinthian capitals, its shrine inscribed with maxims of classic philosophy—γνώθι σαευτών, “know thyself.”

Aï Khānum also bears evidence of a genuine hybrid culture: a statue of the satyr Marsyas, dedicated to the local river god of the River Oxus, by Atrosokes, whose name (“he who shines with sacred fire”) identifies him as a priest of the Persian fire cult. A similar fusion can be seen in the Persian-style pillar which a Greek ambassador named Heliodorus dedicated to the Hindu gods Garuda and Vishnu on his visit to the court of an Indian king, and in the rock edict erected by the emperor Ashoka in Alexandria-in-Arachosia (modern Kandahar), inscribed with a Buddhist message in both Greek and Aramaic.

A Greek king in northern India, Menander I, converted to Buddhism. Buddhists remember him as King Milinda of the Yunani (from Ionian), and the Milinda Panha preserves his conversations with the Buddhist sage Nāgasena. “And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the houseless state, grew great in insight, and himself attained Enlightenment!” Greek Buddhists depicted Siddhartha in the Greek style, in bas relief with realistic human features, and this in turn influenced the art of India.

Will they not consider how camels were created?

How the sky was uplifted?

How the mountains were moored?

How the earth was smoothed?

—The Noble Qur’an, 88:17-20

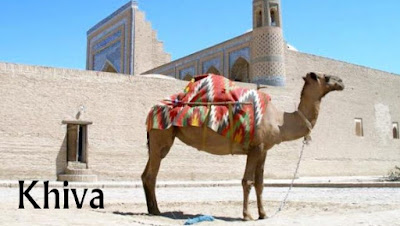

European travelers of the nineteenth century spoke of three forbidden cities: Mecca, Lhasa, and the Silk Road outpost of Khiva, the last isolated as much by the encircling Red Desert as by the violence of Turkmen bandits and the city’s bloodthirsty Khan. Today Khiva is easily reached by rail and road, but passage here, and along much of the overland route, once called for camels.

The camel is “the ship of the desert,” perfectly suited to its inhospitable environment. Spindly legs and shaggy coats insulate her body from the heat radiated by desert sand, while wide-splaying feet keep her from sinking in the dunes and thick eyelashes guard against the glaring sun. Equally marvelous adaptations allow camels to survive long periods without drinking water, mostly by conservation and by a greater endurance for dehydration. (The characteristic humps are not water tanks, as often imagined, but deposits of fat.)

Camels come in two main types: the dromedary of the Middle East with a single hump, and the larger, woolier, two-humped Bactrian camel, a native of the Central Asian steppe better adapted to the cold winters and high altitudes of the region. The latter dominated the Silk Road trade routes for millennia, and it took the Russian railroads of the late nineteenth century and the Soviet highways of the twentieth to supplant it.

Less than a century ago, Soviet artists could not put brush to canvas in Khiva without including a camel as mascot of the romanticized past. Today there is only one: a slumbrous dromedary who carries tourists rather than cargo. Her name is Katrin.

Once in olden times,

In a faery land,

A horseman made his way

Over the thorny steppe.

—Boris Pasternak (1890-1960)

Beyond the Oxus and Jaxartes, the earth stretches out into what the Russians called the Hungry Steppe. Here the riverine farmlands yield to dust, the orchards to desert scrub, and the world vanishes at the horizon without even a telephone pole or a tree to mar its melted curve. As Chekhov wrote, “one drives on and on and cannot discern where it begins or where it ends…”

The Eurasian steppe lies open from the Carpathian Mountains of Eastern Europe to the shores of the Pacific in Manchuria, with little to interrupt its monotony. This latitude shaped Russian history by setting the widest possible limits on its expansion: from the sixteenth century to the early twentieth, the empire grew by 100,000 square kilometers every year. “Measureless immensity flew on: the Empire of Russia.”

The steppe takes on an ambiguous presence in Russian art: sometimes of grandeur and heroism, sometimes bleak and stifling and desolate, sometimes as a projection of an unrestrained national character and destiny, but always a place of weird beauty.

Millions are you—and hosts, yea hosts, are we,

And we shall fight if war you want, take heed.

Yes, we are Scythians—leafs of the Asian tree,

Our slanted eyes are bright aglow with greed.

—Alexander Blok (1880-1921)

The Ural River is not the first boundary between Asia and Europe. Past geographers fixed the limits of the European “continent” at the Don and the Volga. The edge tended to move east, as the settled peoples of the western steppe distinguished themselves from their Scythian forebears.

The Ural River we now use as a marker has its springs in the mountains of the same name—a sparse line of unimpressive hills which supposedly cleave European Russia from the vast Siberian wilderness—and cuts south to empty into the Caspian Sea.

Crossing from one side of the river to the other, do I notice a difference, a sudden shift in civilization? None at all! Young Kazakhs are partying shirtless on either shore, while more conservative generations stroll the shaded embankments in long-sleeves. Change is never as immediate as the lines on maps make it seem.

Up from Earth’s Center through the Seventh Gate

I rose, and on the Throne of Saturn sate,

And many a Knot unravel’d by the Road;

But not the Master-knot of Human Fate.

—Omar Khayyam (1048-1131)

From the oasis towns of Central Asia, the route most often remembered as the Silk Road proceeds across Persia and through Baghdad and Damascus to the ports of the eastern Mediterranean, and thence to Europe. But this way has rarely been the best traveled or the easiest.

Today the difficulties begin in Central Asia, with complicated visas for Azerbaijan, Iran, and especially Turkmenistan, where a tourist visa can cost hundreds of dollars and a 5-7 day transit visa is refused as often as given. The boats which still ply the Caspian Sea offer passage between the east and Baku, but that requires days of struggle in the stifling coastal offices. And then the roads which let onto Mesopotamia and the Levant are an impassable mire of blood.

The most common Silk Roads have always been the safest. They sweep around the mountains and deserts of Persia and the Middle East, either by trundling across the endless northern steppes or by setting sail from China or India to reach the Mediterranean by way of the Red Sea. I have chosen another route, equally old, which heads north from the Caspian via Astrakhan and the Volga River to Russia.

On the Volga, hark, what wailing

O’er the mighty river floats?

’Tis a song, they say—the chanting

Of the men who haul the boats.

Thou dost not in spring, vast Volga,

Flood the fields along thy strand

As our nation’s flood of sorrow,

Swelling, overflows the land.

—Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov (1821-1877)

The Volga is the longest and the largest river in Europe, “a sumptuously dressed, modest, melancholy beauty.” She waters most of Russia’s largest cities, including Moscow, and is as central to the country as the Yellow River is to China.

Modern Volgograd, at a bend in the river, holds a location essential to the northern trade routes. The Volga reaches the Caspian Sea and the Silk Road cities of Central Asia; the Don River flows into the Sea of Azov and thereby the Black Sea and Mediterranean. Here only 100 kilometers separates the two. By only a short portage (traversable today via the Volga-Don Shipping Canal), ships could carry cargo from the depths of Asia to the heart of Europe.

Volgograd has an infamous history under every name but the one it bears now. The Golden Horde established their capital here in a city of tents called Sarai. Ivan the Terrible conquered the area for Russia and built Tsarnitsyn. And nearly two million people spilled their blood here in 1942-1943, when it was known as Stalingrad.

Moskva . . . how many strains are fusing

in that one sound, for Russian hearts!

What store of riches it imparts!

—Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837)

First the river and land routes and then the railways of Russia met in Moscow, placing it at the literal crossroads of Asia and Europe, never fully sure where to belong: to one or the other or both or something apart. “Moscow may be wild and dissolute,” wrote a nineteenth century nobleman, “but

there is no point in trying to change it. For there is a part of

Moscow in us all, and no Russian can expunge Moscow.”

Moscow is the heart of Russia, and the heart of Moscow is its remarkably beautiful Metro. Marble walls and columns, high vaulted ceilings, glittering chandeliers, iron lettering and a nearly complete lack of practical signage—these are not subterranean transit stations but ballrooms, palaces, works of art in themselves.

Stalin hired British engineers and conscripted the best architects and artists in Russia to build the first extravagant terminals at bomb-proof depths, and every leader but Kruschev used the expansion of the subway lines to reaffirm Russia’s “radiant future” (svetloe budushchee). They decorated each station with socialist visions of the proletariat at work, celebrations of martial heroism in 1812 and 1945, and later in a more liberal age with scenes from the novels and plays of the Russian artists after whom they are named.

The Soviets of the second world understood better than we do in the first, where public art has given way to crass commercialism, the role of public spaces in shaping social values. Although a vector for propaganda, the Moscow Metro was free of advertising, and it has remained that way under the Russian Federation. The flash and interference of commerce may have entered Petersburg’s underground and consumed the subways of China, but Moscow’s, like the city itself, delves inexorably into the past.

“Here indeed was Moscow’s paradox,” wrote the cultural historian Orlando Figes—“a progressive city whose

mythic self-image was in the distant past.”

A quiet secluded life in the country, with the possibility of being useful to people to whom it is easy to do good, and who are not accustomed to have it done to them; then work which one hopes may be of some use; then rest, nature, books, music, love for one’s neighbor—such is my idea of happiness.

—Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828-1910)

Tolstoy spent the last years of his life at Yasnaya Polyana, the family estate one hundred miles south of Moscow, plotting Russia’s future from its rural past. He was neither the first nor the last to do so. The Slavophiles of the 1830s came to the countryside in search of the “Russian soul” and a more authentic and moral way of life than that of the Westernized cities. The Populists of the 1870s saw the peasants as natural socialists and took their simple, hardworking economy as a model for a new communal system. Ethnographers, folklorists, and composers of the nineteenth century mined the “rural depths” for cultural relics that reflected Russia’s own unique legacy, unchanged through the centuries and untouched by cosmopolitan currents.

What Tolstoy hated worst was the comme il faut of polite urban society, which cut people off from genuine human interaction. “Here there are no chains,” wrote Viazemsky of the village, “Here there is no tyranny of vanity.” Those in Tolstoy’s train tended to idealize the Russian peasant as a natural Christian, hardworking and happy, and tended also to end their lives embittered by the brutal realities they encountered outside the manor house.

Answer great city:

Where are your glorious days of liberty,

When your voices, the scourge of kings,

Rang true like the bells at your noisy assembly?

Say, where are those times?

They are so far away, oh, so far away!

—Dmitry Vladimirovich Venevitinov (1805-1827)

How different would Russia be, had the peaceful and democratic trading city of Novgorod, and not Moscow, brought it to union?

Novgorod was a city of wood, with wooden churches and houses built along streets of pine logs laid side-by-side. Its place on the River Volkov made it a center of trade between the Baltic Sea and the Russian hinterland, and later a member of the Hanseatic League. Until the victory of Moscow in the fifteenth century, any Novgorodian could ring the bell that summoned the assembly, the veche, with the power to appoint officials, create laws, and decide questions of justice.

To reformists of the nineteenth century, the bell of Novgorod symbolized the possibilities for democracy and liberty in Russia. It proved that Russia was not autocratic by nature but by the caprice of history.

Proud charger, whither art thou ridden?

Where leapest thou? and where, on whom

Wilt plant thy good?

—Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837)

Peter the Great built St. Petersburg as a “window on to the West,” a projection into sweat and stone of his effort to reconstruct Russia as modern European nation. The city emerged from the Neva’s marshy delta on the land reclaimed from the sea at the cost of 30,000 peasant lives—progressive Enlightenment ideals and callous disregard for life.

Peter’s modern capital “eclipsed at once” Old Muscovy and the traditions embodied in its wooden homes and gloomy churches. Unlike other European capitals, which accumulated over centuries if not millennia, Petersburg was completed in fifty years, under a singular architectural vision, on a vast manmade canvas between sea and sky. Gogol called Petersburg “an accurate, punctual kind of person, a perfect German,” and Dostoevsky called her “the most abstract and intentional city in the whole round world.”

Theatrical urban planning balanced grandiose and baroque architectural ensembles with avenues, squares, parks, and canals of equal grandeur. These canals also separated the aristocratic boroughs from the teeming mercantile areas like the Haymarket of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

Rules enforced the use of stone and classical facades along the Nevskiy Prospekt. Yet here, too, Russia showed through: different crews starting at either end of what was meant to be a straight three-mile stretch somehow got the line wrong and left the whole vision of Enlightenment order unalterably bent.

Many runes the cold has told me,

Many lays the rain has brought me,

Other songs the winds have sung me;

Many birds from many forests,

Oft have sung me lays in concord;

Waves of sea, and ocean billows,

Music from the many waters,

Music from the whole creation,

Oft have been my guide and master.

Sentences the trees created,

Boiled together into bundles,

Moved them to my ancient dwelling,

On the sledges to my cottage,

Tied them to my garret rafters,

Hung them on my dwelling-portals,

Laid them in a chest of boxes,

Boxes lined with shining copper.

Long they lay within my dwelling

Through the chilling winds of winter,

In my dwelling-place for ages.

Shall I bring these songs together,

From the cold and frost collect them?

—The Kalevala (19th century)

The blue-black waters of the Baltic Sea, enveloped by the bent arm of Scandinavia, have lured millions to trade and adventure. Medieval merchants set sail and lowered oars from Novgorod, Danzig, Lubeck, and Visby, through the Danish Straits to the North Sea, while Vikings and Wendish pirates launched their longships from the innumerable coves and estuaries which break the Baltic coast.

Today eight nations rim the Baltic; one of them is Finland, whose frigid swamps and jagged coastline often served as arena and prize for the contests of Sweden and Russia. The former built a fortress in Helsinki, the latter developed a regional capital here, and the Finns “did not bend under oppression” but finally won and bravely defended their independence in the twentieth century.

No sooner did he find himself surrounded by this curiously dignified ancient amalgamation of gables, spires, arcades, and fountains, no sooner did he feel the wind blowing in his face again, that strong wind which carried with it a delicately sharp aroma from distant dreams, than a veil and tissue of fog seemed to befall his senses . . .

—Thomas Mann (1875-1955)

Lübeck remains a mostly medieval city. The bell towers of St Marien, St Petri, and St Jakobi overshadow a dense maze of streets on an island ringed by the River Trave and by the remains of ramparts and of warehouses for the salt, grain, fur, and amber that made up the bulk of northern trade.

The city-state was a prominent member of the Hanseatic League, the commercial organization which dominated international trade in Europe in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. Among its many innovations was a weapon we recognize today: the Verhansung or commercial boycott. The Hansa had no constitution, but Lübeck was the home of its accumulated body of custom and jurisprudence and the most common place for the Hansetag or general assembly.

The Hanseatic League survives in elegant stone cities like Lübeck, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gdansk, and in the idea of an international civilization based not on language, race or religion, but on mutual interest and shared priorities.

Homesickness! That long

Exposure to misery!

It’s all the same to me—

Where I’m utterly lonely

Or what stones I wander

Home by, with my sacks,

Home that’s no more mine

Than a hospital, a barracks.

It’s all the same to me, what

Faces I bristle among, a lion

Captive, what human crowd

—as it must do—thrusts me on,

Into myself, individual feeling,

From the pole, a Kamchatka bear;

Where I fail to fit (and won’t try!),

Where I’m debased: I don’t care.

I won’t let the milky call

Of my native language tempt me.

It’s all the same to me in what

Tongue they misunderstand me!

(By what readers swallowing

Newsprint tonnage, gossip’s grime…)

They belong to the twentieth century

While I’m—before my time,

Petrified, like a log left

From an avenue, let fall.

They’re all the same—it’s all

The same—perhaps most of all—

What was native to me—of all.

All the signs and tokens, there,

All the dates—a hand erased:

The soul once born—somewhere.

My land cares so little for me

That even the keenest sleuth

Could traverse my whole—spirit!

And find no birthmark, in truth!

Houses alien, churches empty,

All—one and the same—to me:

Yet if by the side of the road

A particular bush shows—rowanberry…

—Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

Even before the GDR and the FRG split it in two, Berlin was a living encounter between east and west. Three million Russians fled their homeland in the wake of the 1917 revolution, and Berlin was the first major center to receive them—the only European capital with ties to Soviet Russia. Berliners began calling the Kurfürstendamm the NEPskii Prospekt, from Lenin’s Neue Ökonomische Politik. The glut of Russian shops and cafés left a permanent mark on the western suburbs.

By the early 1920s, Berlin was the adopted home, however temporary, of many of Russia’s most talented artists, including Tsvetaeva, Berberova, Nabokov, Stravinsky and Rachmaninov, Gorky and Bely and Pasternak, who brought with them their language, their sensibilities, and their nostalgia for an utterly vanished past. Russian language publications outnumbered German ones and put Berlin at the center of a culture in exile.

German artists found inspiration in the Soviet avant-garde, which broke the rigid cultural and intellectual bonds that had propelled Europe into the self-annihilation of the Great War. The First Russian Art Exhibition (Erste russische Kunstausstellung) in 1922 brought constructivism, suprematism, and Malevich’s Black Square. And then—nationalism, totalitarian rule, concentration camps, and the new wave of artistic experimentation broke in both countries.

Know’st thou the land where the lemon-trees bloom,

Where the gold orange glows in the deep thicket’s gloom,

Where a wind ever soft from the blue heaven blows,

And the groves are of laurel and myrtle and rose?

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Strasbourg’s name is a Gallicized formation of the German Straßburg, “city of roads,” roads leading west into France and east across the Rhine. This city and the surrounding region of Alsace is where the two cultures meet and, like the ecotones of nature, marks the line of an often violent and chaotic dialectic.

From the Middle Ages to today Strasbourg has changed hands a half dozen times between these two powers. It is now the easternmost center of France, but also a symbol—as much for its Franco-German culture and cuisine as for the institutions, the University, the Council of Europe, and the European Parliament, which are seated there—of the continent’s newfound unity, and of the creative and constructive possibilities of collisions like this.

Fileur éternel des immobilités bleues,

Je regrette l’Europe aux anciens parapets.

Eternal wanderer of the unmoving azure,

I miss Europe with its ancient ramparts.

—Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891)

Everywhere in what was once an empire there are mementos of “the grandeur that was Rome.” The Romans built in monoliths, in massive and enduring designs allowed by innovations in concrete, the arch, the vaulted ceiling. The ruins seemed nothing less than the work of giants to those who inherited them, who had lost much of what made Rome grand.

Medieval streets, squares, and churches were conditioned by the preexisting structures of the imperial cities on which they were built. Roman baths were repurposed as baptismal fonts, gladiatorial arenas (like the one in Nîmes) as marketplaces, and expansive urban villas as apartments. Houses set in the vaulted arcades of Roman circuses took on a regularity in their dimensions unlike the haphazard medieval type.

These ancient foundations are still to be seen, in the walls of newer structures or set apart by modern archaeology: a permanent reminder of the unity which much of Europe once shared.

‘O brothers who have reached the west,’ I began,

‘Through a hundred thousand perils, surviving all:

So little is the vigil we see remain

Still for our senses, that you should not choose

To deny it the experience—behind the sun

Leading us onward—of the world which has

No people in it. Consider well your seed:

You were not born to live as a mere brute does,

But for the pursuit of knowledge and the good.’

—Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)

The ships of Aragón, built in the Royal Shipyards in Barcelona, resembled more the Argo or a Viking longboat than the frigates and galleons which in the sixteenth century began to replace them. The Aragónese galley was long, slender, and low to the water, with banks of oars to propel the vessel even when the sail could not. Until advancements in navigation and sailing allowed ships to brave the open seas in any wind, the oar-powered galley could outrace and outmaneuver larger sailing ships, and the disadvantages of its shallow draft and low clearance, which limited it to coastal areas, did not weigh against it.

The galley dominated the sea-lanes of the Mediterranean—raiding, fighting, trading, and transporting—until the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. By then the four bars of Aragón had flown over the Baleares, Sardinia, Sicily, and Naples, and Barcelona was an entrepôt on par with Genoa and Pisa. Gangs of captives and criminals had replaced the chattel slaves which in Christian lands as much as Barbary were chained to the oar. Both the galley and the Spanish Empire kept a place on the water until the nineteenth century put an end to both.

‘What giants?’ asked Sancho Panza.

—Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616)

At first several hundred press together, all in white slacks and uniform shirts emblazoned with the sign of Sant Magí, whose day it is. They form the piña, that is the bulk, and atop that platform of human heads forms up the folre, the cover, like the second layer of a wedding cake. These men and women wear the black sash called the faixa, sometimes twelve meters in length, to add another foothold to the shoulders and knees for those who climb next.

Before that the cap de colla, the leader of these castellers, must decide whether to continue or not. A structural weakness even in the piña can collapse the whole tower. All along he has been shouting directions, as fans shh the drunken crowd so he can be heard; he nods and issues another. The band starts up the Toc de Castells, with snare drums and the piercing oboe-like shawm of Catalonia. Now there is no stopping the castellers.

The cuatros, the groups of four, go up and link arms atop the folre, then atop each other. Each casteller in the bottom cuatro could stand in for Hercules, and each cuatro is more slender than the last.

When the cuatros stand four-by-four, four children start up for the highest levels, looking like portobellos in their thick cloth caps and like monkeys with their quick vertical movements. The dosos (twos) link arms, the aixecador (riser) locks them together, finally the enxaneta (rider), the smallest of the gang, straddles the aixecador. She raises her hand to make the four fingers of Aragón, level with the rooftops, and the crowd erupts.

The enxaneta slides down the cuatros, somersaults from the folre over the heads of the piña, and leaps ecstatic into her mother’s arms. The disassembly of a castell is as dangerous as its construction. Already the men of the bottom cuatro grit their teeth, their eyes bulge, and every muscle seems to shake, but still they manage to grin as victorious castellers swing down from above.

The castell is a Catalan tradition of the early eighteenth century, vital today as the Catalan try to distinguish themselves from the Castilian culture most associated with Spain. In Tarragona, the four local colles castelleres begin practicing in February for the August festival, which lasts all afternoon and includes many variations on the cuatro tower. The best colles will build towers at the Concurs de Castells, held biannually on the first Sunday of November in Tarragona’s Roman arena.

When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies?

Perhaps to be too practical is madness.

To surrender dreams—this may be madness.

Too much sanity may be madness—and maddest of all:

to see life as it is, and not as it should be!

—Dale Wasserman (1914-2008)

On 15 May 2009, Spain’s Indignados, also called 15-M, began to occupy public squares across the Iberian peninsula. They protested against new austerity measures, against the global banking system that forced austerity on a nation still reeling from the 2008 economic crisis, the unfettered capitalism that caused the crisis, and the corrupt two-party political system that removed the fetters. It's a familiar agenda—inspired by the Arab Spring in 2008, inspiring in turn the Occupy movement of 2011.

As many as eight million of Spain’s 45 million people participated. In Zaragoza, they occupied the Plaza del Pilar and set up tents beneath one of the grandest basilica in Spain. The Indignados opened nightly discussions on political and economic issues, attended by thousands of locals who had never trusted the party-based process. The same thing happened in all of Spain’s largest cities, then many of the world’s.

In Spain, however, the popular activists persevered. Pedro Santisteve, a human rights lawyer, emerged from the Indignados movement to become mayor of Zaragoza in 2015. Similarly rooted left-wing coalitions took power in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, and Cádiz. The Indignados shattered the two-party system, but also lost much of their revolutionary inertia by joining the banks, the bureaucrats, the police, the church, and the rightist People’s Party on the long list of Spanish institutions.

A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa,

Born in the West, far from the land of palms.

I said to it: How like me you are, far away and in exile,

In long separation from family and friends.

You have sprung from soil in which you are a stranger,

And I, like you, am far from home.

—Abd al-Rahman (731-788)

The Palacio de la Aljafería in Zaragoza is the most significant architectural relic of Muslim civilization in northern Spain, and also a perfect symbol of Iberia’s historical fortunes. Abu Jaffar al-Muqtadir—ruler, poet, astronomer, and mathematician—built the palace as a second residence outside the city, around an older tower which he used as an observatory. His halls surrounded a paradise of fountains and fruit trees, with horseshoe-shaped lintels, Quranic quotations inscribed in alabaster, and floral and geometric patterns in red, green, blue, and gold.

After a Navarrese bastard (re?)conquered Aragón, Christian kings took over Abu Jaffar’s elegant home. Pedro IV used the tower as a library, and he hired a Muslim resident or mudéjar, from the word for “domesticated,” to oversee the construction of a symbolic second floor over the north wing. The mudéjar were simply better builders than the uncivilized northerners: their material expertise extended beyond stone and mortar to brick, plaster, carved wood, and glazed tiles. They filled in the space between the coats of arms and the Renaissance grotesque and Gothic features of the Kings of Aragón with unmistakably Islamic ornamentation. This syncretic style endured until a 1526 decree compelled all mudéjar to be baptized or else depart, for more tolerant lands in North Africa and the Middle East.

The tower became a seat of the Inquisition, who held court beneath the Arabic inscriptions of the mudéjar to accuse converted Jews and Muslims of secretly practicing their original faith; then an anachronistic feature of the sixteenth century fortress, when soldiers bivouacked in Abu Jaffar’s palace and cooked in his mosque; then a setting for Antonio García Gutiérrez’s 1836 play El trovador, which Verdi made into a libretto; and finally a twentieth century museum, while the neighboring offices of the Inquisition were torn down and replaced by the offices of the regional parliament.

There are no other countries like Spain.

—Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)

Hemingway once called Spain “the last good country left.” His experience as a correspondent in the Spanish Civil War and his clear Republican sympathies inspired both his greatest novel (For Whom the Bell Tolls, 1940) and his only play, but his love affair with Spain began two decades earlier in the arena of Pamplona.

Hemingway visited Pamplona nine times in his life, most often during his Roaring Twenties residence in Paris. The annual journey to see the bullfighting festival of Sanfermines became the setting for The Sun Also Rises (1926) and made Hemingway an aficionado of the brutal, blood-splattered sport. He wrote a manifesto about it called Death in the Afternoon (1932), and later covered a rare mano-a-mano contest between two matadors for the Life magazine story “The Dangerous Summer” (1959), written on his last trip to the city and only published after his death.

By then he hated it. Twenty years in Franco’s grip had changed the country he loved, but Hemingway himself had changed Sanfermines by making it one of the best-known festivals in the world. “It is all there, as it always was, except forty thousand tourists have been added. There were not twenty tourists when I first went there.” They come to stay at La Perla or the Hotel Quintana, to dine at Café Iruña and Botín, to run from the bulls down Calle de la Estafeta, while the statue of “Don Ernesto,” which the people of Pamplona erected by the bullring gate in 1968, looks on impassively.

O, kaletarroak, txapela erantzi

inoiz mendira joatean,

baserri zabal urtez jantziak

aurrez aurre ikustean.

O, countrymen, take off your beret in respect

whenever you go to the mountains

and see the farmhouses

before you, shrouded in time.

—Ignacio Eizmendi “Basarri” (1913-1999)

Euskara, which we call Basque, is a language isolate whose origins are a mystery. It shares nothing with the Romance languages that surround it, as the reader of the above poem can probably tell, nor does it have a place in the Indo-European family tree. It lives in Euskal Herria, the Basque Country, straddling the western Pyrenees with one foot in Spain and a big toe in France, and the dominance of these has required a constant struggle for cultural survival.

Euskara’s twentieth-century decline began with urbanization, which brought people from the farmhouses where the language was preserved to the cities where Franco was constructing a Spanish national identity. Basque students learned in Castellano, the language of empire and romances which we call Spanish, and the Castillian teacher would give a rap to the head at the softest whisper of their native tongue.

From these conditions, and with plenty of European examples, emerged Basque nationalism. At its most positive, the nationalist spirit saw a revival of the improvisational performances of poetry called bertsolaritza and the annual contests called txapelketa. At its most dubious it established Euskara as the primary teaching language in Spain’s Basque region and produced a generation of Spaniards who do not speak Spanish. At its most morally bankrupt is the ETA, the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, an armed separatist group founded in 1959.

Can nationalism enrich a society without poisoning it? In an age when every two weeks sees the death of a language, could Euskara have survived without the ugliness of ethnocentrism?

But will God indeed dwell on the earth? behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee; how much less this house that I have builded?

—1 Kings 8:27

Gothic architecture evolved in France out of the Romanesque style, where height came at the cost of thick stone walls, massive columns, and small windows. The Gothic use of ribbed vaults with pointed arches and of flying buttresses allowed for lighter walls, with space between the stone for vast ensembles of stained glass. The result was a temple of space and colored light meant to evoke the New Jerusalem.

Of the 200 Gothic cathedrals to be built in Europe in the late medieval period, the Cathedral of León (along with those of Mertz and Chartres) has the most impressive use of stained glass—around 1,800 square meters in 723 windows, almost all from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, in three successive levels all around its cross-shaped interior. “This Cathedral has more glass than stone.”

The position of the Cathedral and its windows transforms sunlight into a liturgical performance of the Christian story, told within a linear reality of weightless figures and bright hues. Images of Christ in the apse face east to catch the light which dispels darkness. The noontime glare filters through depictions of the apostles in the southern facade, while Old Testament prophets in the northern wall receive only a reflection of the light. The setting sun meets a rosette in the western gable, where a portrait of the Virgin amid the Last Judgment releases the light at the end of the day.

Gothic verticality depends on a careful balance of forces, easily upset by unstable foundations, the use of bad quality stone, or errors in calculation. The León Cathedral suffers all three, “like a sick person who is stable but requires constant care.” The last major renovations in the nineteenth century required the dismounting of thousands of glass panes, fourteen years of scaffolding, and decades of painstaking work. That the creaking stone heights have not collapsed is miracle enough.

Every man follows his own path in search of

grace, whatever that grace may be,

a simple landscape with the sky overhead,

a certain hour of the day or night,

two trees,

three if they are painted by Rembrandt,

a sigh,

without our knowing whether this

closes or finally opens the path

or where the path may lead us,

whether to some other landscape,

hour,

tree, or

sigh.

—José Saramago (1922-2010)

With the miraculous discovery of the body of Saint James (Santiago in Spanish) in a pre-Christian mausoleum beneath the present Cathedral, Santiago de Compostela became one of Christianity’s most important pilgrimage sites, behind only Jerusalem and Rome. A pilgrimage is a ritual journey, a search for purification, enlightenment, and salvation. In the self-abnegation and ceaseless discipline that this journey requires, in the movement from ordinary life to some timeless place, it is an allegory for the spiritual journey that passes within from confusion to insight, from death to deathlessness.

Early pilgrims to Santiago, and legend makes Charlemagne the first, followed whichever of the existing Roman roads, dirt paths, or game trails would carry them, which by the eleventh century had consolidated into regular routes. Today there are 39 Caminos de Santiago in the Iberian Peninsula, and many more stretch out from as far away as Paris and Moscow. The Camino Francés, which begins on the French side of the Pyrenees, accounts for two-thirds of today’s traffic.

These pilgrim paths inspired the creation of highways and bridges, churches and hospitals, cheap hostels called albergues which remain a regular feature of the pilgrimage, and institutions like the Confrérie de Saint-Jacques. Early pilgrims lined the way with their own sweetly blasphemous shrines to the rivers and the wind, with the stone mounds called milladoiro, and with other remnants of pre-Christian ritual. And always the yellow arrow marks the way.

The World Wars and the rise of fascism in Spain emptied the roads to Santiago, but Paulo Coelho’s 1987 novel The Pilgrimage and the Xacobeo ’93 cultural festival helped to renew interest. The number of pilgrims to register in Santiago (a poor measure but better than none) increased from 2,500 in 1986 to 262,000 in 2015. Today the albergues overflow with guests, and every hour in the Plaza del Obradoiro, at the footsteps of the Cathedral, you can observe the arrival of a dozen pilgrim bands who come cheering into the square and of a few solitary travelers who sit down on the flagstones, remove their boots, stare up at the gothic towers that have taken weeks or months to reach, and feel the peace that was within themselves all along.

My words rained over you, stroking you.

A long time I have loved the sunned mother-of-pearl of your body.

I go so far as to think that you own the universe.

I will bring you happy flowers from the mountains, bluebells,

dark hazels, and rustic baskets of kisses.

I want

to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees.

—Pablo Neruda (1904-1973)

Hazul Luzah has often had to paint over his own art, to return abandoned buildings to the barrenness of the tomb. As a child he looked outside and saw a canvas in Porto’s narrow, sloping streets. His vibrant murals—water and wind, shamanic figures, an invented calligraphy often mistaken for Arabic, and a robed feminine figure—appear overnight in alleyways and empty lots and endure sometimes a week and sometimes until the building is renovated and the city is “allowed to breathe.” Urban art is by its nature ephemeral, anonymous, and empowering.

Iberian graffiti grew as a natural outlet for public expression after Portugal’s 25 April Carnations Revolution (1974) and the death of Franco (1977) put an end to the stifling repression of the fascist state. The Portuguese, with a sensitivity for free speech born of its opposite, tend to forgive and preserve graffiti with political content. The mottoes of the revolution linger on urban walls, with fresh paint all around them. Urban artists still call themselves writers even after the shift from felt-tip markers to aerosol and from adage and verse to the figurative visual idiom of America.

Today graffiti is everywhere in Iberia. The 2008 financial crisis, which caused both political turmoil and a proliferation of abandoned and incomplete buildings, incited something like a renaissance. The funicular, which carries tourists up to the Porto Cathedral, can be repainted one evening and once more covered in tags by sunrise. The owners of huge urban canvases often prefer to commission a mural from a well-known writer as a sort of security, because the one thing artists respect is art itself.

Ó mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

São lágrimas de Portugal!

Por te cruzarmos, quantas mães choraram,

Quantos filhos em vão rezaram!

Oh salty sea, how much of your salt

Are tears of Portugal!

To get across you, how many mothers cried,

How many sons prayed in vain!

How many brides were never to marry

In order to make you ours, oh sea!

Was it worth it? Everything is worthy

If the soul is not small.

Who wants to go beyond Bojador,

Must go beyond sufferance.

God gave the sea peril and abyss,

Yet upon it He also mirrored the sky.

—Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935)

When Vasco da Gama first reached the Malabar Coast of southern India, he sent ashore two mariners to reconnoiter. A pair of Tunisians, who had taken the usual sea route via Alexandria and the Red Sea, happened by these Portuguese and were astounded. “What are you doing here?” they asked, speaking Italian, to which the Portuguese replied, “We come in search of Christians and spices!”

Religion and commerce would inspire a century of unprecedented exploration and expansion by Europeans, and by the Portuguese first of all. Following Bartolomeu Dias’s journey around the treacherous Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and Da Gama’s landfall in India a decade later, Pedro Álvarez Cabral and Amérigo Vespúcio mapped out Brazil, Alfonso de Albuquerque conquered Ormuz, Goa, and Malacca, Jorge Álvarez went to Canton, Ferdinand Magellan circumnavigated the earth (under the flag of Spain), Dom João de Castro annotated the route to Goa, and Saint Francis Xavier built up Christian communities in East Asia.

No matter the mission the sailors inevitably stuffed the holds (and their own bunks and bags) with black pepper from Malabar, cinnamon from Ceylon, and cloves, ginger, and nutmeg from the Moluccas, all worth its weight in gold in the markets of Europe. The spice trade westward was small when compared to that of India and China, and yet it was so potentially lucrative that generations of Portuguese braved the hazards of the trip and made Lisbon one of the wealthiest cities in Europe.

Ah, here arrives a fleet of these intrepid caravels! They fire a salute to the Torre de Belém to announce their safe return, which the investors have prayed for as intensely as any wife or mother, and to let us remember the obsolescence of the Silk Road. Who now would take the transcontinental route, what with the collapse of Pax Mongolica, chaos in China, desertification in Central Asia, and the rise of a hostile Turkish state in the eastern Mediterranean? Da Gama found his own way to Asia and, in the name of Christians and spices, began an age of empires, an age of slavery, rape, oppression, and unrestrained commercial exploitation from which the world is still recovering.

And I was alive in the blizzard of the blossoming pear,

Myself I stood in the storm of the bird-cherry tree.

It was all leaflife and starshower, unerring, self-shattering

power,

And it was all aimed at me.

What is this dire delight flowering fleeing always earth?

What is being? What is truth?

Blossoms rupture and rapture the air,

All hover and hammer,

Time intensified and time intolerable, sweetness raveling rot.

It is now. It is not.

—Osip Mendelstam (1891-1938)

And with a flight out of Madrid my four-month, 11,000 mile (18,000km) trip comes to its finally airborne end. I had meant to see the Silk Road, the bridge of East to West, and I saw that it did not end at the Caspian Sea, nor with the voyage of Vasco da Gama.

The Silk Road of history was neither one nor the other. Traders carried silk but also spices, chemicals, metal and leather goods, and paper—the last by far the most culturally significant as it allowed for the mass distribution of knowledge. There was no single road, but rather a tapestry of ever-shifting paths stretched between rivers and mountains and oasis towns. The classic route drew from Xi’an, crossed the Yellow River and the Gansu Corridor, arced around the Taklamakan to Kashgar, then the Pamir Knot, the Central Asian steppe, the Mediterranean and the Baltic.

We follow in our minds eye the caravans from start to end, but for most of its history the Silk Road was host to a local, subsistence, barter-based economy: carpets, copper, iron, lead, Chinese steel, deerskin boots, ammonium chloride for use in metallurgy and textiles, white and yellow powder for cosmetics, aromatics and incense, gold, silver, silk, steppe horses for the Chinese army, and cattle. Most goods were locally-made everyday necessities, like bowls, pack saddles, wheat flour, and tea, rather than luxury items destined for Europe. Most long-distance trade in silk came from the Chinese military, and then only on a few occasions. The sea routes to the Indian Ocean and Red Sea were always easier.

And yet the transit between continents, which the Silk Road represents, has created the modern world. Persistent traffic across great distances, however small the scale, brought Buddhism to China and Zen to Japan (and the Bund to Shanghai, and liberty to the Hansa, and Hemingway to the bullring). Massive movements of people introduced the realistic facades of Alexander’s Hellenistic colonies to religious art in Asia (and the guitar to America, and the camel to Australia, and Picasso to Paris).

Places of cultural exchange and transformation exist everywhere: not just in the notorious diversity of Kashgar and Samarkand, but in the apparent homogeneity of Xi’an and Berlin. In every city along my road, East and West meet and merge and lose their meaning. The integration of the Other is already achieved in the lives of individuals, families, and whole communities who live between the cultures we commonly regard as fixed, exclusive, and essential.